By Toyin Falola

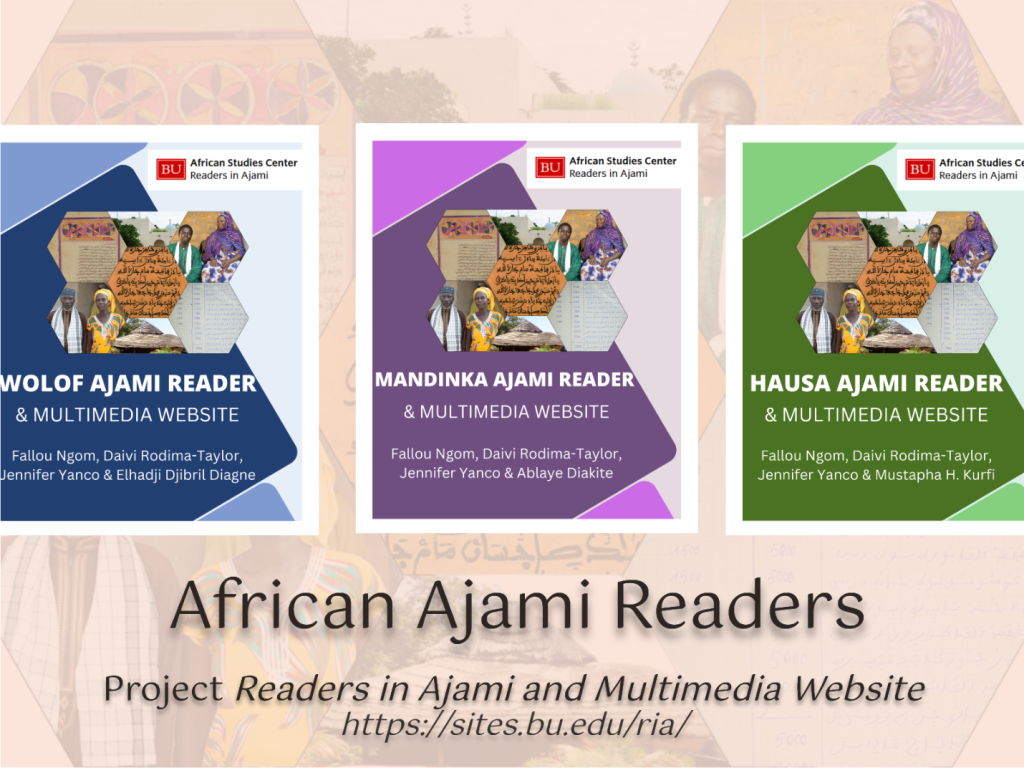

It is a pleasure to witness the fruits of the long labor of Professor Ngom and his fellow researchers, recently released in three volumes, African Ajami Readers, covering Wolof, Mandinka, and Hausa (https://sites.bu.edu/ria/). Professor Ngom and I have discussed this project for nearly twenty years, even sharing updates about his travels to Senegal, Casamance, and Guinea. I congratulate Professor Ngom, Daivi Rodima-Taylor, Jennifer Yanco, and Elhadji Dibril Diagne. I will surely put the volumes to good use. Based on his Ajami research, we invited him to the University of Texas to speak, and he also enlightened the public about it at Lagos State University and Adeyemi College of Education.

In recent times, African studies and history have been subjects that have pounded into the consciousness of different scholars across the globe, occasioned by the laurels and accolades that African writers have gotten. These writers have not only written on discourses to express their thoughts, but they have done so in consonance with African culture and identity. Wherever there is an African thought, concept, or philosophy, we are sure to find an African identity. It is one thing to create awareness and a different ball game to sustain such awareness such that it promulgates a new order whereby African studies are elevated to the highest echelon of academia. It would be very untruthful not to concede that African studies have suffered relegation; for one, the diversity within African culture makes it somewhat arduous to conceptualize some of the discourses. Also, the infusion of colonial narratives has, in some ways, diluted African instinctual cultures.

As scholars, we recognize our role in the decolonization of Africa, and it is not solely the responsibility of the government and its parastatals to wage this war. To this end, it is crucial to proliferate African studies in some undiluted forms. The Ajami text presents a unique opportunity to achieve this. Utilizing Ajami sources can galvanize efforts to energize African studies. Ajami represents a process of linguistic adaptation, wherein the Arabic script is modified to write various non-Arabic languages. Its usage predates colonial rule and, as a result, colonial administrators familiarized themselves with Ajami and used it in their correspondence with local emirs.

Ajami texts provide Indigenous narratives on culture, social life, politics, and more, which are often overlooked in colonial archives. Notably, Lord Lugard employed a similar strategy in his conquest mission of 1900. Realizing that Hausa was the dominant language, he sought to strengthen his grip on local rulers, particularly in Hausa communities. Therefore, Hausa was transcribed into Roman, and this Romanized Hausa was termed “Boko,” meaning Western education. This methodology allowed for effective communication between the colonizers and the Hausa subjects, similar to the use of Ajami texts.

Ajami texts encompass sociological, historical, and cultural knowledge largely unexplored by elite scholars writing in Arabic and European languages. These manuscripts cover diverse subjects, including science, philosophy, diplomacy, and literary works such as folktales and narratives. Additionally, the texts contain discussions on pharmacopeia and medical conditions like stomach ailments and rheumatism. Ajami serves as a medium for scholarship across all fields of intellectual inquiry. This raises a critical question: how come such a rich body of academic investigation exists, yet we still suffer from a lack of information on African studies?

A significant disconnect exists in contemporary scholarship between Arabic scholars and their counterparts proficient in various African languages. Many scholars who specialize in Arabic are often not well-versed in the linguistic nuances of African languages, while those fluent in African languages often have little knowledge of Arabic. This linguistic divide poses a major challenge in studying a vast corpus of historical documents inscribed in modified Arabic scripts. These documents are essential to understanding the cultural and historical contexts of African societies; however, they remain primarily neglected and underexplored in archives scattered across the continent. As a result, the rich intellectual heritage encapsulated in these Ajami texts risks being overlooked. Nonetheless, it is a call for the academic exploration of these texts on a much broader scale.

It is commendable that the University of Boston has incorporated and sponsored research on Ajami texts. The team is led by the esteemed Professor Fallou Ngom, a key contributor to the study of Ajami texts in elucidating African history and culture. According to Ngom and his team, “This project aims to enhance the comprehension of Ajami literature in sub-Saharan Africa by conducting a comparative analysis of four prominent West African languages: Hausa, Mandinka, Fula, and Wolof.” The Ajami literary traditions of the Sahel offer valuable insights into the historical narratives and lived experiences of local populations. Although these systems emerged from a shared purpose of disseminating Islam, each Ajami framework has evolved along a distinct path, influenced by localized cultural, social, and political dynamics.

One of the stumbling blocks of African studies has been the enduring influence of colonial narratives. Decolonizing African studies as a discipline requires unearthing ancient landmarks of African identities that can offer an Afrocentric perspective of the discipline, hence the prominence surrounding Ajami texts. In retrospect, the proliferation of Islam in Africa, particularly in the Sahel, was successful. However, Arab Muslims still consider African Muslims inferior to them, a perception that has etched its way into politics, governance, and education, despite African countries’ independence from colonial fetters.

We would be simple-minded to say that the investigation of Ajami texts in varied concepts in the four languages is just a pedagogical and linguistic exercise. In reality, it spans far beyond that–it is an investigation into the history of language and culture, as well as the methods through which Islam meandered its way to non-Muslims on the continent and its widespread practices. This exercise would expunge the stigmatization that these regions face from colonial narratives, often drawing bias from the practice of religion. This alone is a victory for African studies, which has existed for some decades (post-World War II) but has faced literary challenges further exacerbated by neo-colonialism, globalization and cultural hegemony.

Over the years, another challenge of African studies is its reliance on European archives, which have always systematically presented narratives that would engender Eurocentric views even in African discourses. It should not come as a surprise that a system built in Europe would not sponsor African ideologies at the expense of European dogma and methodology, as everyone promotes their own. Recordkeeping systems are inherently biased. These systems perpetuated a distorted portrayal of social order, one that colonial administrators used to maintain governance through violence and control. As representational frameworks, colonial archives reflected a particular culture and the infrastructures supporting it. Consequently, archival institutions played a crucial role in shaping the ideological frameworks of national histories and may have acted as active facilitators of colonial oppression.

Ajami manuscripts offer a valuable alternative by articulating indigenous perspectives on significant historical events, political systems, and social structures. These texts serve as vital records of oral traditions, local governance, and quotidian life in African societies, predating European colonial intervention. Much of the Ajami scholarship during colonial Africa comprised Arabic and Western scholars rather than African community members. However, after the demise of the colonial African state, there was a massive entry of African scholars into Ajami scholarship. This shift helped to refine the information in the Ajami archive, allowing us to truly understand the enormous impact and contributions of the Ajami archive in uncovering Afrocentric themes and ideologies and its preservation.

It is not enough to create a consciousness around a discourse that diminishes over time. A system that sponsors its sustenance and vetoes its eradication should be implemented. This is an opportunity for African scholarship to preserve the ordinances of African study and history through the Ajami archive. We are often guilty of delimiting African studies to history, literature, and language. History, however, presents a much more persuading narrative, noting that Egyptian medicine and innovation are the blueprints, or to be cosmopolitan, the patent through which most of the miracles of medicines and the wonders of engineering have been discovered.

The Ajami archives hold evidence supporting the above assertions. Texts on pharmacopeia, botany, and indigenous healing practices exemplify the extensive knowledge held by African communities regarding the medicinal properties of plants and their applications for ailments such as gastrointestinal disorders and rheumatism. These writings illuminate Africa’s rich tradition of scientific inquiry, contesting the prevailing notion that the continent’s scientific knowledge was exclusively imparted through colonial interventions.

Despite its value, Ajami texts may continue to be marginalized because of language limitations and inaccessibility. While efforts have been made to explore these texts in four languages, it is a humble submission that we employ more African scholarship to go beyond this milestone. With thousands of indigenous languages in Africa, exploring just four languages barely scratches the surface. Another perspective to this linguistic approach is preserving indigenous African languages, a fundamental aspect of African studies.

The digitization of the Ajami archive would help address its inaccessibility. The more proliferated the texts become, the more African scholarship can interface and interact with rich historical narratives. This would help bridge the lacuna and divide in African scholarship, moving away from the “hush-hush” topics on African studies, history, and progression.