PART 1:

“OAKS OF RIGHTEOUSNESS”: BISHOP KUKAH AND HIS NATION

By Toyin Falola

“…provide for those who grieve in Zion – to bestow on them a crown of beauty instead of ashes, the oil of joy instead of mourning, and a garment of praise instead of a spirit of despair. They will be called oaks of righteousness, a planting of the Lord for the display of his splendour.”

Isaiah 61:3 NIVUK

Please, don’t tell me that you have not heard about the synergy between the Church and the State! But you know the difference between God and Mammon? Not yet! What about peace and war? Evil and Good? You probably always have a readymade answer: material gains, political gains, control of the people politically through the church. Whatever form the answer takes you, it would most definitely be the variants of the Yoruba maxim, “Erée kí l’ajá ń bá ẹkùn ṣe?” Loosely translated: “What friendship exists between the dog and the tiger?” The dog or tiger here is unknown, but while the Church and its stewards are often associated with spirituality, purity, and redemption, the state, politics, and its major actors are often associated with dirt, blood, corruption, cunningness, evil, and death. In short, while the church would lay claim to light, the state would be forced to settle for darkness. Like the dog and the tiger, the Church and the State are located in the space of tension. As far back as the 14th century, the greatest philosopher of that era, Ibn Khaldun, warned the clerics to be careful of politicians unless both can guarantee good governance. The binary opposition between good and evil guided Ibn Khaldun’s stance.

Debates on the relationship between the Church and the State did not start in Nigeria, and is indeed an old idea in Africa. It predates the medieval period. This was an era of rampant conflicts of interest, authorities, autonomy, etc., between the state and the church. Many great philosophers tried to propose theories aimed at the ultimate solution, but in creating balance, Thomas Aquinas edged out predecessor thinkers when he asserted that the Church should have no business within political or secular activities of the State. In the same manner, the State should not interfere in ecclesiastical matters related to the Church.

Father Kukah

Father Kukah

II

“Pure religion and undefiled before God and the Father is this: To visit the fatherless and widows in their affliction, and to keep himself unspotted from the world.” James 1:27.

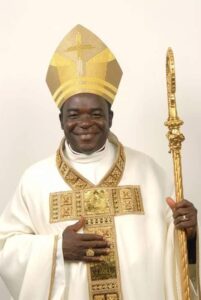

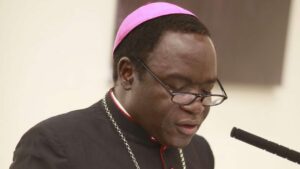

From several indications, it is not an ideal or a common phenomenon. Still, there is someone who does it better, if not greater. He combines both admirably well and emerges from it with respect intact from all and sundry, against all odds of strong Nigerian ethnoreligious dichotomy. His name is Bishop Matthew Hassan Kukah. This doesn’t mean he is washed clean from controversies as palm oil sometimes spills on his white garment. You can hardly be in the limelight, especially in the Nigerian clime, without one wahala (trouble) or another. Father Kukah, with his exceptional stint, has been no exception—last December, he was soaked in the juice of ìjọ̀gbọ̀n, (double trouble), thrown into ọbẹ̀ẹ́ gbóná (hot soup), pelted with stones carved out of Aso Rock, and tormented by the affliction of ọ̀rọ̀ ọ̀ràn (verbal violence). Only that he, without doubt, has done admirably well to manage a relatively smooth relationship between the State and the Church, even if not always satisfactorily. And this is why I can proudly call him my friend—for his love of Nigeria and Nigerians—with all its complications and provocations.

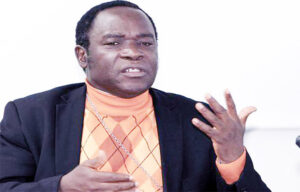

Father Kukah isn’t just excellent and admirable as a public figure; he is equally a very great man. We share a lot in common. His quest for development, good governance, social justice, and the pursuit of scholarship, ranks very high among people with a selfless passion for humanity. You could say it is this desire and passion that led him into entanglements with political affairs. Of course, as the saying goes, if you want to make a change, you would need to wield power. Kukah does not contest political positions nor court power; neither does he refuse to contribute or reject the calls to serve in public capacities, which affords him the chance to effect change, no matter how little.

More interestingly, another striking thing about Kukah, which you can say perhaps could have engineered our friendship, is his love for scholarship. Kukah is one of the finest writers I know. He sends his draft essays to me to read, and he is forever appreciative of my comments. We once co-authored a book, and we have a plan to co-author yet another. The creative imaginations that come with him narrating non-fictitious experiences make his works and writing powerfully beautiful to read. I ask him how he does that, a porridge-style format, combining within a page, profound ideas and the most delightful sentences with elevating stories.

He has contributed massively to Nigerian humanitarian development, principally with his involvement with the Ogoni in the Niger-Delta, a story he is still currently telling in a book-length manuscript that has been my privilege to read. Having directly and semi-directly served virtually all presidents of Nigeria in the fourth republic, Kukah perhaps has a book in vogue on leadership and the limitations of Nigeria’s Fourth Republic leaders. With his experience and craft, it would be great to examine one of the pertinent problems of development in Nigeria, just as it is across Africa: the leadership deficit.

Similarly, through accounts of his sterling contributions to public service, some of which he already chronicled, future generations could gain insight into some of the controversial periods since the return of democracy in 1999, and likewise, the process of democratizing institutions, bringing justice and development to minority groups in the country. Indeed, he is a verifiable authority to analyze based on authentic personal experiences and not mere conjectures or theoretical frameworks along with the gap between policy drafting, adoption, and implementation. This is especially the case having served in many committees, such as the Investigation Commission of Human Rights Violation (1999-2001); Secretary for the National Political Reform Conference in 2005, after which he was “hijacked” by President Obasanjo—who he reckons with as a good friend—to serve as the presidential facilitator for the Ogoni-Shell Reconciliation. Trust my friend, he did not stop his job at just facilitating a reconciliation to ensure peace for the government; he encouraged further clean-up of Ogoniland, which he brought in the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) to oversee it, thus invoking a credible additional international outlook to the process. During the short tenure of President Yar’Adua, he functioned in the committee that looked into electoral reforms as set up by the federal government. As an academic, apparently, the intellectual production of Father Kukah’s active years in public service vis-a-vis his and the committees’ contributions, problems existent, factors responsible, problems solved, problems unsolved, factors inhibiting. etc. would make for a much-needed first narrator, eye-witness account for peace and conflicts studies in Nigeria and Africa at-large. Beyond his credibility as one who was thoroughly part of several processes with the subject matter, he also similarly collected relevant degrees: a master’s in Peace Studies from Bradford in the United Kingdom (1980) and a Ph.D. in Oriental and African Studies from London a year later.

Combine his religious dispositions, teachings on peace and unity across ethnic groups, religions, and every other form of differences and discrimination with his vast educational prowess and contributions to peace and democratic development in Nigeria, you have Father Kukah. Considering his unsolicited direct access to power, especially during President Obasanjo’s tenure, one would have naturally expected pecuniary material gains for Kukah. Not him! Rather, he has earned the respect of many for his selfless contribution to the development of Nigeria’s nascent democracy; he is selfless to the point of using his own personal funding for some of these projects, to the point of risking his life in a very hostile environment amidst enmity, criticism from anti-democracy and anti-development elements in the country. Father Kukah is that very rare personality with whom you can boldly say that this world would have been a better place if everyone was like him. His intelligence, diligence, commitment, humility, conflict management, and diplomatic skills make him one who is sorely needed and is lacking in several leadership positions across the country.

Kukah

Kukah

III

Do not be afraid of those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul. Rather, be afraid of the One who can destroy both soul and body in hell. Matthew 10:28.

Kukah

Kukah

How about his audacity? Despite serving directly an Obasanjo who cemented his place in Nigeria history as the feared Ẹbọra Òwu for being very commanding, assertive, and authoritative, Kukah didn’t hesitate to speak up to his boss when wrong; and of course, not without his exceptionally benign demeanor. Most recently, he condemned Buhari’s nepotism, risking the wrath of the North where he has lived all his life, barring his education outside the country or assignments. Perhaps, it is Kukah’s religiously inclined belief that only the body can be killed, not the soul or faith in the Lord; or, in the words of the Reformer Martin Luther, not the truth. In this regard, protecting him means no harm could come to him. Whatever gave him the courage, Kukah hasn’t hesitated to speak when needed while he shies from the limelight when not required. He is well-known for his brutal honesty and blunt comments, remarks, responses to posers or situations requiring them. The oft used Sir John Dalberg-Acton’s maxim, “power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely,” perhaps undoubtedly fails the application test when Kukah is concerned. Impressive!

Beyond the aforementioned, Kukah is a scholar par excellence with several publications in books, journals, articles, rejoinders, paper presentations and even research works bordering on religion, politics, democracy, power, and social justice, which adds to the body of knowledge production in and about politics in Nigeria. This is a rare feat for a cleric! With the vast body of works credited to Kukah exhibiting his intellectual prowess, it is perhaps not surprising that he is near-perfect in distinguishing between the State and the Church. And while he has a very close relationship with both, he ensures he knows where the line is to be drawn such that the Church does not intrude into politics and the State does not interfere in the church.

Kukah’s brilliance at serving both without one interfering in the other and with his life conduct serves to exemplify him as a man of his very teachings. It also means he can stand the test of fire, water, and wind and still have his white linen as clear as crystal, untainted. His respect and integrity remain intact. His guiding principle was divined centuries before he came to this sinful world, and this should be his epitaph:

“But whoso hath this world’s good, and seeth his brother have need, and shutteth up his bowels of compassion from him, how dwelleth the love of God in him?” 1 John 3:17.

God dwells in Bishop Kukah because he cares about his brother, Chukwu; his sister, Ayesha; his uncle, Ogundipe; and his cousin, Bello. Hassan loves Muslims—the signal message of his name. Matthew loves Christians—the caring message of his name. Kukah loves the worshippers of African indigenous religions—that is the message of his nativity. Call him the “love of God,” the epithet of his epitaph.

Please join us for a conversation with Bishop Matthew Hassan Kukah, the Bishop of Sokoto.

Sunday, March 7, 2021

5:00 PM Nigeria

4:00 PM GMT

10:00 AM Austin CST

Register and Watch At:

https://www.tfinterviews.com/post/bishop-kukah