By Toyin Falola

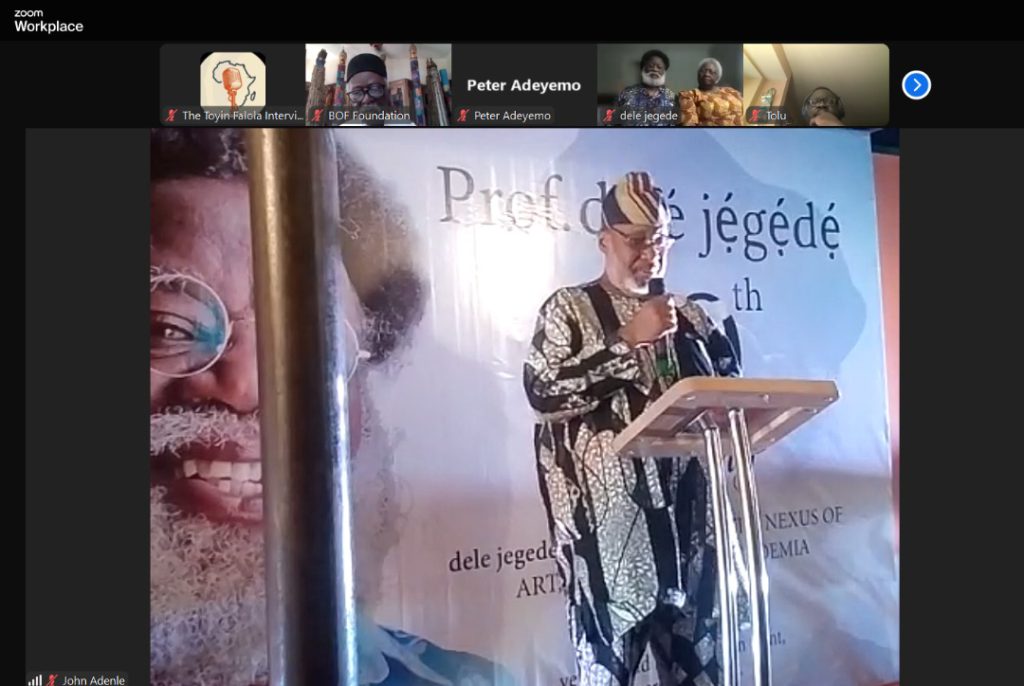

It was a privilege to have participated in the one-day symposium on “Dele Jegede at 80: Examining the Nexus of Art, Activism, and Academica, held on April 26, 2025, at the University of Lagos.” Jegede’s Old Testament beard added color to the event, although no divine vision was brought from the wilderness.

As I pen my thoughts and join the host of family, friends, colleagues, and well-wishers in celebrating an eminent personality in Nigeria’s world of contemporary arts and outside its borders, I couldn’t help but recall the beauty of human creation. Humans, unlike other living entities, have enjoyed the gift of nature more in many ways. Even with our sporadic scientific engagements in today’s world, we can all agree that nothing has spoken more than creativity about the brotherhood, joys, and sorrows humans have shared, portrayed, and exemplified for many generations.

The point here is acknowledging the rare opportunity we enjoy as humans to remember, reflect, and celebrate the past and memorable moments in unique ways. When humans come together to bask in the memories attached to these events, one cannot embrace these opportunities, especially when life remains a journey of the unknown.

My thoughts wavered a bit as I recalled the past decades and the exemplary lives of an icon whose impacts undeniably have been felt by many beyond count. I view this writing more as a duty than a form of courtesy, as expected during celebrations. I see this as a duty to tell the tales of a rare personality whose career as a painter, teacher, and cartoonist has reshaped and given a new voice to the world of visual identity.

As I write this on Baba Dele Jegede’s 80th birthday, I feel compelled to tell the story of an excellent, humble beginning in the southwestern part of Nigeria, down to the North, and then overseas to the United States of America. Indeed, it is a pleasure to have lived and experienced the greatness that followed Dele Jegede as he continued his journey of impact, even in retirement. Before the likes of Dele Jegede, the arts have always been viewed as an escape from reality and a way to lose oneself in the abstract. However, a new perspective arose, with Dele and others redefining perspectives by providing the arts a voice that communicates to the eyes, brain, heart, and soul.

The dynamics of the nuance of Ikere Ekiti, where Dele Jegede was born, contributed to his communal discipline training and the Omoluabi orientation. It pushed him towards self-discovery and deeper into the abyss of abstract conceptualism. The immediate post-colonial atmosphere of the nation was also instrumental in creating an ideological sphere where Prof Jegede could explore his perspective on life, skills, and talent. Seeing these attributes, his father allowed him to further his education, a luxury many kids did not have. More importantly, you must understand that Prof Jegede held through with his commitment to development and ensuring that his skills define the society, not the society caging his skills. To own this, while exploring music and drawing, he hawked drugs and other things in Ikere and assisted his father in sponsoring himself.

Not absolved from the childhood tantrum of a boy child, the young Jegede had an eventful childhood hustling between farm work, church activities, and education. From an early age, the icon explored his immediate environment, building a curiosity about the world around him. From scribbling on the walls at home and tearing in class to help make charts for schoolwork, Jegede began a journey in building a natural artistic inclination that eventually led him to study creative art at Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria, Nigeria, in 1973.

In the following years, Jegede was already tilting towards the elitist artistic qualities he exalts. Professor Jegede’s love for knowledge and exploration of perspective has taken him across the world. To the United States of America, he brought his talent, his enthusiasm, and his sense of desire. Indiana University, Bloomington, was the institution from which he graduated with a Master’s and a Doctoral degree in art. It was there that he studied art history under the skillful direction of Roy Sieber. This encounter profoundly altered his work life and his conceptual approach to art. Because he held these qualities, Jegede was unstoppable as he embarked on a reinvigorated quest to ensure that the arts have a voice. With these qualifications, Jegede was unstoppable as he embarked on a renewed journey to provide a voice for the arts. His doctoral work on Trends in Contemporary Nigerian Art centred on the art of Bruce Onobrakpeya and Twins Seven Seven, was the first ever work of art centred on contemporary Nigerian art.

On the other hand, Professor Jegede did not need to acquire any form of official schooling to earn our respect as the famous artist we honor today. His commitment to integrating his academic knowledge with the realities of Nigerian culture, history, and politics stands out as one of the most significant reasons why he is honored today. His contribution to the Daily Times in Nigeria as a cartoonist configured the public perspective of his as a social critic who employs his skills to shape society. His artistic appeal to the masses made his work popular and acceptable.

With the mastery expected of a genius, he introduced comic shows like “Kole Omole and Flower Power” into public view. Each theme depicted contemporary social issues. For instance, in Kole Omole, he portrayed a precocious five-year-old whose sharp questions and innocent observations held up a mirror to the excesses and absurdities of Nigeria’s military regimes and failing systems. His works were beyond jokes, jest, and sheer entertainment. Through careful selections of words and a perfected line of thought, he subtly highlighted social menaces like corruption, oppression, and the decay of public institutions, all while staying true to the pulse of the people. Jegede’s work was about telling stories.

The significance of Professor Jegede’s stories gives me a reminiscence of what should and should have been, especially the world and Africa’s reaction to skill and creativity. The contemporary universe of humans is gravitating towards boring circles of imposed duties, timelines, suffocating spaces, and rejected dreams and aspirations, if we still remember what that means. As Africa grows, following the influence of globalization, patterns are drawn for the scope and extent of an African child’s imagination. We already know that you must go to school, write exams, and seek jobs that shape your future in the world. The African universe today now expels the possibilities of a “character.” Our time is sold, conditioned, or controlled by the capitalists who rule the world.

The measure of success is now bedded on the parameters of these Western apparatuses; where you fall short, you are either dejected or rejected against the social order of things. While a service-oriented society is not strange to the pre-colonial African societies, skills and expertise, and their adjoining freedoms, were of greater importance than those services. When you learn one, you do it for a while to set out on the odyssey of life’s uncertainty. If you made it, that was fine; if you did not, that was too.

Skill and natural creativity were the hallmarks of precolonial Africa, which formed the core of African society. In the current regimented society, society must let it take its course, develop, and nourish. It was used in many ways to address different life and cultural concerns. The Ikere society allowed his talents to flourish right from when he could hold a pencil. His mother and father of late memories wielding skills that weaved his foundation into reliability and expansion of his imaginary scopes, enabling him to conceptualize even the most abstract.

We must also understand that sometimes, the essence of these skills and expertise, as shown by Prof. Jegede, is not only for personal aggrandizement but also for community development, advancement, and criticism. As an artist and cartoonist, Dele did not hold back in criticizing the deplorable state of Nigerian and African politics, reminding the people of the importance of their social bonds and mandates. His work was during the civil war and the intermittent interruption of Nigerian democracy by the military junta.

While working with the Daily Times and the Sunday Times, his artistic work and cartoons manifest a courageous stance against dictatorship. Kole Omole and many other works show his rejection of the junta, corruption, and bad politics.

The lesson is that the nation needs to allow creative freedom, promote talents and skills, and incorporate them into Western education and contemporary learning curves. However, whether skilled, service-oriented, or talented, one must remember the social duty we owe to Africa and our origins. Professor Dele Jegede has been notable for using his creative prowess to advance society, and through his pedagogy, he has passed down valuable social lessons to us all.

.