By Olayinka Oyegbile

Medicine is my lawful wife, and literature is my mistress. When I get [fed up with] one, I spend the night with the other – Anton Chekov

The symbiotic relationship between writing and medicine has been a subject of study from time immemorial. This is because the men and women with the scalpel and stethoscope have proven to be adept writers who with their training have been able to delve deep into the soul of their characters. No one has been able to ascertain whether their training has in any way put them at a vantage position to write about human foibles and triumphs.

However, whether the training has done this or not, the world of creative writing, in fact, writing generally has been enriched with the writings of these men and women who have been trained to search the human body and diagnose them of various ailments and prescribe steps to healing them.

Some of these have gone beyond prescribing tablets, injections or of cutting up flesh to heal but have gone to the intricate world of writing to heal the world through their writings and helping to bring sense to a troubled world. Among these have been medical doctors such as Anton Chekhov (1860–1904), the Russian writer who not only made success as a short story writer but as a dramatist, and his compatriot Mikhail Bulgakov (1891–1940), who also made a roaring success as a medic and a writer. Also, across the gulf is Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930), the immortal creator of that all season’s detective Sherlock Homes. Not to be left out are John Keats (1795—1821), who rather than wearing his stethoscope plied his trade in words through poetry. W. Somerset Maugham (1874–1965), qualified as a doctor but dropped the certificate over the huge success of his debut novel Of Human Bondage, which has never gone out of print. The Afghan novelist Khaled Hosseini (1965 – ), whose debut novel The Kite Runner and subsequent ones have been published to world acclaim also trained as medical doctors.

On the African continent, there has been a surfeit of these too. The Egyptian feminist activist Nawal el Saadawi (1931 -2021) belongs to this class of medical doctors turned writers, so is Lenrie Peters (1932-2009) of The Gambia. In Nigeria, there are scores of them such as Dr Wale Okediran, who is now the Secretary General of the Pan African Writers Association (PAWA). In fact, they are too numerous to list. In this league now is Ike Anya, a public health practitioner who has detailed what could be considered as a rich manual of what it takes to train as a medical doctor in Nigeria in the nineties.

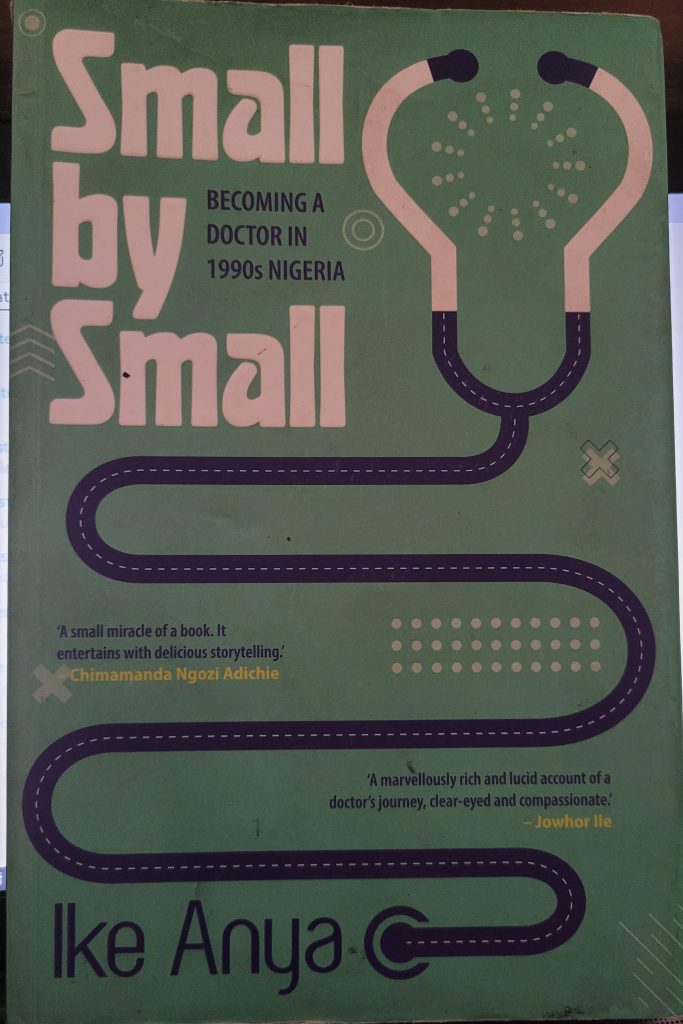

Anya is not however new to creative writing. His writings have appeared in newspapers and magazines both at home and abroad as well as in anthologies. He is also a co-editor of a collection of short stories from Nigeria. His 2023 memoir, Small by Small is an intimate memoir of what it was like to be a medical student in Nigeria in the nineties. He has chronicled a story which no doubt would resonate with many Nigerians who grew up during the time he writes about. The nineties were the period the country went through successive brutal military dictatorships.

The writer through his eyes and how he perceived events is able to take the reader, even those who were not privileged to witness the events narrated, to follow the stories as they unfold. Starting from his little beginning as a secondary school student to getting to the final years of secondary education and deciding what to choose as a course of study in the university. The reader is able to follow him as he navigates his life choices and the role his grandmother, who incidentally gave him the title of the book, played in his life.

The struggles and the nerve-wracking moments of waiting for medical school examination results, failure of crucial courses and the need to resit such exams are narrated with candour and equanimity without blaming his teachers or other factors for his own failings. Despite the tough times and stresses he underwent he was able to capture some fun moments that enliven the scary and tough moments.

Demonstrating how easy humans are to cast stereotypes, he narrates an encounter between him and a consultant who on Anya’s failure to answer a question satisfactorily wanted to know where he hails from. When he told the consultant he hails from Abiriba, he riposted, “What on earth is an Abiriba man doing studying medicine? You are just taking up a place that should be occupied by someone who is actually going to practice medicine. All you Abiriba men, once you get your degree, you will head to Aba, to open a market stall selling textiles or Okrika clothing.” (p73). So much for stereotypes! Thank God the Abiriba man is not in Aba today selling Okrika clothing but plying his medical trade as a consultant in public health medicine in the United Kingdom and also a visiting lecturer at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine! Never neglect the days of humble beginnings, if he had allowed that putdown to get at him, where would he be today?

Through this memoir, readers who are not in medical line are also able to glimpse the subtle or behind the white coat rivalries that exist among medics. Another consultant also had a dig at one of Anya’s classmates when he also failed to answer a question. The consultant had asked, “What field of medicine would you like to specialize in?” The obviously harassed student replied, “Internal medicine.” But the consultant was unkind by telling the poor guy, “No. You can’t do medicine. With your huge size and small brain, you should specialize in orthopaedic surgery, pure carpentry, where muscles will be most useful.” (p74). Imagine. Such comic relieves make reading of this book exciting and not bugged down by medical jargons.

The book is laden with interesting stories and encounters which shows that doctors and medical workers know a lot and keep troves of secrets about their patients. Perhaps this is part of what helps some of them who turn out to be writers to write with some uncommon human understanding. Reading his views about miracles, infertility and so on reminds me of Lola Shoneyin’s award-winning novel The Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives. A patient had come to see one of Anya’s lecturers, a consultant obstetrician. She had been examined and adjudged fit to be a mother. The husband was convinced to surrender himself for medical examination. When he did, according to Anya “His sperm count results are recorded in the folder: the single word ‘azoospermia’ written in capital letters at the end. Unusually, he has had additional tests, including a testicular biopsy. They all indicate that he will never be able to have children.” (p119).

However, years later the wife came back when Anya and his colleagues were students. She had had two babies! Miracle? Perhaps, according to a very active member of an evangelical student fellowship. The mystery for the students was however solved (sort of) by the consultant obstetrician, who cleverly tore off the husband’s result attached to the back of the case file and told the students, “Perhaps it is indeed a miracle. But if it is not, who am I to pour sand in their gari.” (p120). He was not ready to confront the husband with the fact that the two babies might have come from a surrogate father unknown to the man!

Anya’s Small by Small reminds me in no small measure of Tracy Kidder’s Mountains Beyond Mountains, which chronicled the experience of Paul Farmer a Harvard-trained doctor. Anya has through this book given an engaging and interesting insight into what it takes to be trained as a doctor during his time. He writes with the clinical finish of an accomplished surgeon, weaving stories of politics, social realities and military tension of the nineties with a tapestry of elevated language that is captivating and engrossing. Masobe Books by publishing this and other books of recent has shown that its editors have eyes for talented writers whose stories are great and able to affect their world.