Review by Jumoke Verissimo

Title: The Strange Moon of Yenagoa

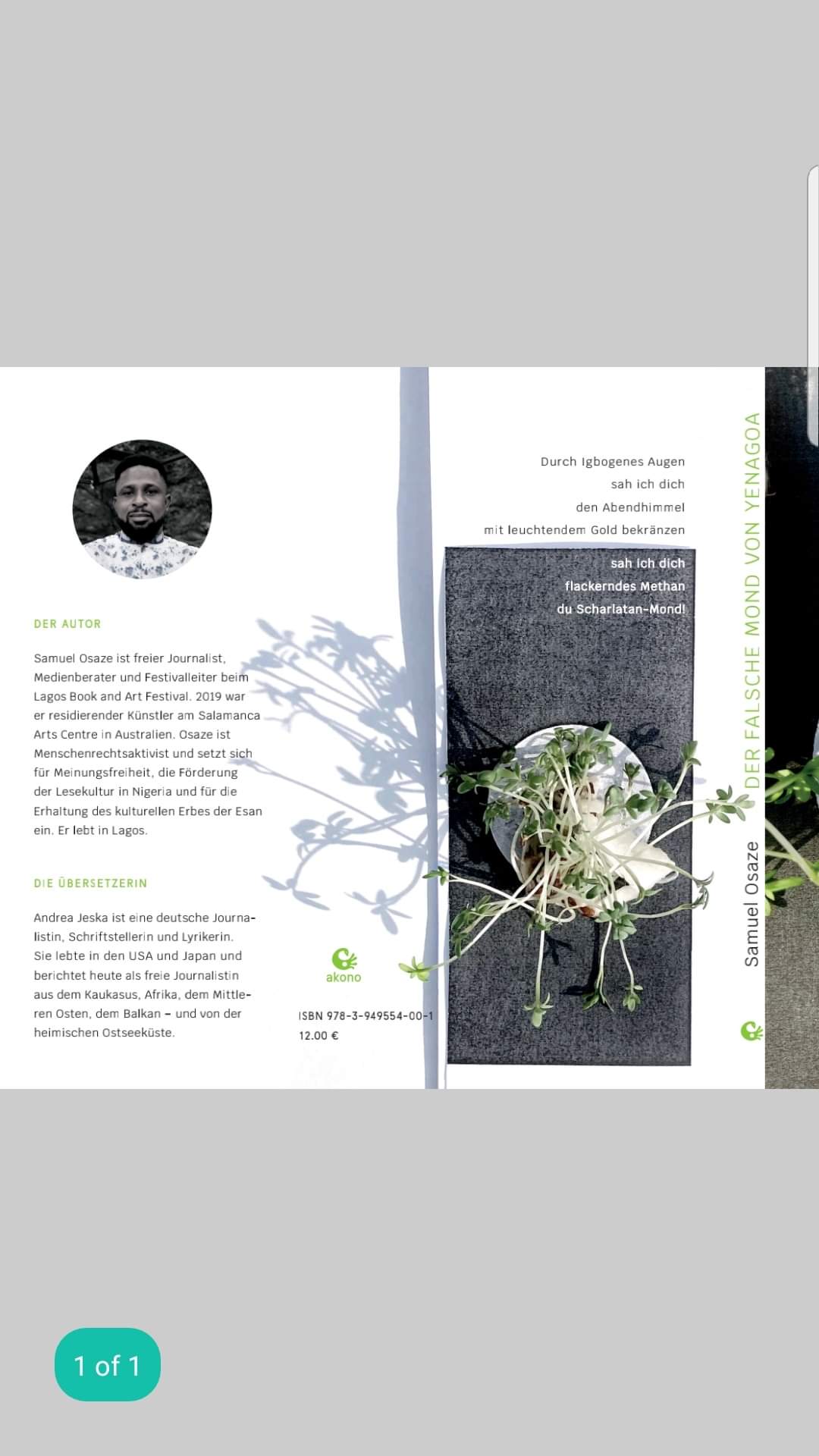

Author: Samuel Osaze

Publisher Akono Verlag, Leipzig, 2021

Samuel Osaze’s The Strange Moon of Yenagoa conveys the Nigerian youth’s never-ending dissatisfaction, anger and relentless bitterness over the state of their nation. Osaze joins a select group of poets, including Akeem Lasisi, Rasaq Malik, Olajide Salawu, Gbenga Adeoba, and others, in reimagining traditional aesthetics through the use of images elicited by oral poetics. Osaze’s poetry seems to be influenced mainly by his Esan and Edo heritage, which serves as a platform for expressing his emotions.

Osaze’s poetry collection is a grim indictment of rejection and abandonment by past leaders, translating Nigeria into a body whose pain belongs to the later generation. The introductory poem to the collection, “The slave-driver,” establishes the poet’s discontent, which runs throughout the book. The slave-driver, as Osaze describes, is “a beast that sips from/ Lamb’s blood and feigns deaf ears/To the fists of hunger/Drumming the walls of empty bellies…” (16). Osaze’s poetry, among other vivid imagery, captures the sense of disillusionment and futility of hope in his depiction of the young as “a vast rich field made barren by livid locusts.”

The poet’s entire work is characterised by an accusatory tone (which, in a sense, conveys the tempo of grievances that are held even when unspoken by the Nigerian youth). However, in a few instances, the poet’s fury is mitigated by his awareness of culture’s sustaining power, demonstrating that not everything is corrupt or despondent. The poems “Upon Seeing an Esan Maiden Dance” and “The Needle Doesn’t Pound Yam,” both in the fourth section of the book, laud the rhythm of a dancer and how this becomes a means by which optimism approaches the spiritual. The fourth section is where the poet looks at dancing as a way to enter the spiritual world in search of personal and, possibly, national rebirth. This section symbolizes how the only thing that works in the country is entertainment and the arts.

While Osaze does a good job of conveying the plight of Nigerian society and the despondence of her youth in his poems, the collection seems to strive a little too hard for fluency. Perhaps this is because the oral form, pursued in writing, is not fully explored. It is important to note that the book’s concept and the premise are sound, and there are a few memorable lines, but the writing elements could be better refined. We can begin with the use of oral poetics in his writing. Typically, oral poetry forms in most Nigerian ethnic groups rely on precise wording that does not lose meaning in the description of the subject matter. For example, the poem “Slave-driver” could benefit from word economy so that the reader is left to understand the agony of unappreciated labor as the poet intends. While delivered verbally, oral poetry attempts to say a lot in a few words. The oraliters who perform these poems understand that words have the power not only because of the image they reveal but also because of their ability to appeal to emotions by revealing something new to the reader while leaving more to the imagination. Because Osaze’s poetry aspires to translate the oral form onto a page, the reader expects a presentation and organisation that mimics a performance on the page. Not necessarily by regurgitating traditional oral poetry elements, but by creating an original delivery of the poem to the reader in which his words linger beyond their theme. The poem “Punch the air at my coming,” for example, has so much potential in the way it begins, “Take me back where I came.” Still, the subsequent lines “tracing ireful root to crotch/of the mother stem, where I supped in fresh breath. . .” veer into a metaphor that perplexes the reader to the point where the poem’s objective is lost.

In terms of form, it is not entirely evident why poems in the collection are aligned to the right. This alignment does not help the readability of the poems and it distracts. Also, while the idea of publishing a bilingual book is sound in and of itself, the collection’s layout detracts from the reading experience. Some compromises may have been made to include two languages in this bilingual book. The reader feels they are missing out on some of the book’s content because some sections were not completely translated. The book, for example, begins with an introduction written in German. The absence of a translation of the introduction makes it impossible for an English reader to access the poet’s reflections on the poems or the background that led to the poems’ creation.

Nonetheless, Osaze’s book is a valuable contribution to the poetry community in Nigeria. He joins contemporary poets from Nigeria, examining the overall experience of young people afflicted by years of poor leadership, which has extinguished their vision of being Nigerian both individually and collectively. From Rasaq Malik’s exploration of loss in its many manifestations, Saddiq Dzukogi’s use of poetry as meditation for grieving, Ndubuisi Aniemeka’s lamentations of shrunken dreams to Romeo Oriogun’s examination of the transition and transformation of the Self, both inside and outside Nigerian borders, the focus of these poets remains to showcase the perplexity over the Nigerian state. Within and outside the borders of Nigeria, the despondence over the nation’s neglect of its “over-caged, citizens of rage,” as Osaze describes, continues to dominate recent works of poetry. With preparations for the elections, Osaze’s poetry is useful for listening to the nation’s pulse at this time. It sheds light on the known and unknown burdens that fall disproportionately on the shoulders of Nigeria’s largest population—the youth.

*Jumoke Verissimo is the author of two acclaimed poetry collections and a novel, A Small Silence. Her most recent book is a children’s picture book, Grandma and the Moon’s Hidden Secret, also available in Yoruba.