The world is like a Mask dancing. If you want to see it well, you do not stand in one place ― Chinua Achebe

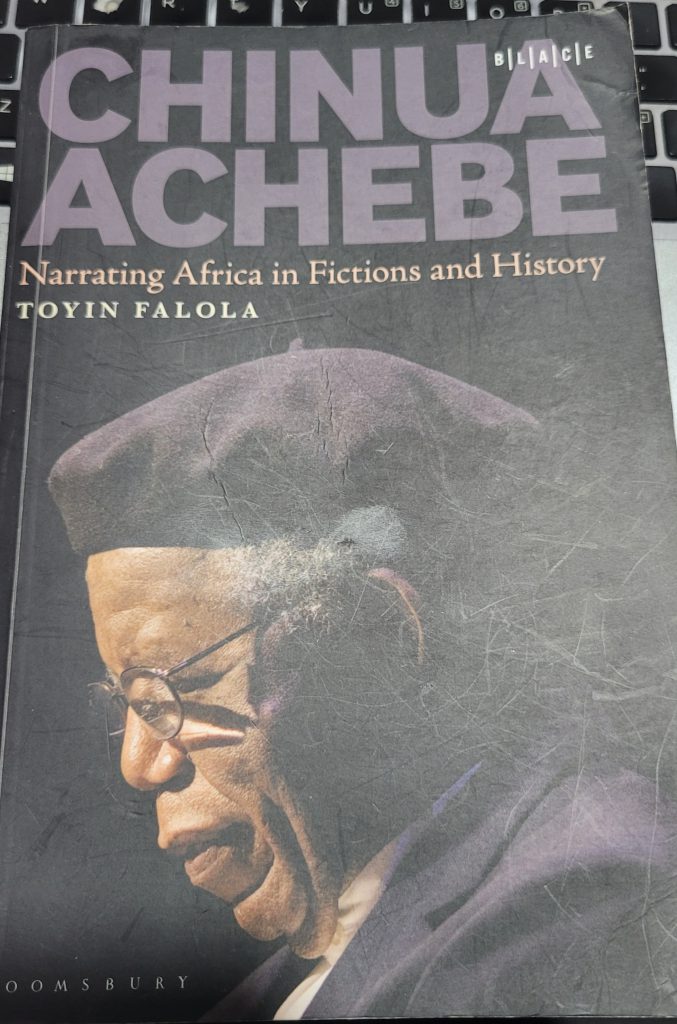

(A review of Chinua Achebe Narrating Africa in Fictions and History, Toyin Falola, Bloomsbury Academic, 2024)

The status of Chinua Achebe in the pantheon of world literature is not in doubt, and for a respected historian and scholar of Prof Toyin Falola’s stature to turn his lens on him is not a surprise. In Chinua Achebe: Narrating Africa in Fictions and History, the respected historian has given new interpretations and perspectives to the works of the renowned writer. In dissecting Achebe’s works in twelve solid chapters, readers and scholars are taken on a new journey of rediscovering what might be hitherto unknown about the master of the rt of storytelling.

A casual glance at the title of the book might make one think: is there anything new that could be written about the bard of African literature? However, under the critical lens of Falola, there are countless things to be written.

The opening chapter ‘The scholarship on Chinua Achebe’ is a detailed review and look at tons of books and ideas that have been written about the man Achebe. In dealing with this chapter, the breath and volumes of works from various sources that have been written about the writer are given considerations and dealt with to establish the premise for the book and also show how this particular one is going to take the study further to “show a degree of interdependence between the man, the writer and his works.” (p27)

In chapters such as ‘The Life and times of Chinua Achebe’ and ‘Precolonial life and colonialism in Things Fall Apart’ (chapters two and three), Falola devotes these to examining Achebe’s life as a student, writer and the influences that led him to his choices of and themes. His upbringing and the life of his people were the raw materials that led to his direction in later life. His view about the life of his people and the need to correct the wrong pictures that have been created by colonial writers was the kickstart for his ambition to tell the story of his people and correct wrong views.

But the idyllic past was not a raw material for painting a picture that was non-existent. In his other novels, Achebe was able to bring to the fore the stark realities of post-colonial life that was bequeathed to his people. The fourth chapter which deals with the novel No Longer at Ease, is a chronicle of how an ailing nation fresh from colonial independence tries to navigate the new challenges. According to Falola, “The narrative of a nation in distress …was not at the time to tell the story of Obi alone but to chronicle the foundation of the problems that Nigeria was to face in the future.” (p100). Most of these are manifesting today in various forms: ethnicity, corruption, looting of resources etc.

Falola takes each of the novels by Achebe and tries to give new insights to the problems tackled according to their time and how they all relate to the present predicaments of the nation and the African continent at large. The issue of religious conflicts in Arrow of God are all traced to the various sources even before the advent of colonialism. In affirming that the history of conflicts in the country was not entirely new, Falola writes, “It was after colonialism and independence that the people of Nigeria started to live as citizens under one nation ruled by natives of the constituents as one. Now, it is important to remember people lived together based on shared cultural values before colonialism. Hence, after the colonialists had forced these people of totally different cultural backgrounds to live together as one, several instances of crises and uprisings in different parts of the country occurred.” (p113). Some of this later day crises are series of religious riots across the country, Boko Haram and others. Achebe foretold all these in almost all his novels and essays tracing it all to lack of effective leadership.

Politics and the military take the centre stage in chapters six and seven. In examining Achebe’s most prophetic novel, A Man of the People, Falola asserts, “Achebe was more akin to the role of a medicine man, given the role his works play in dissecting and interpreting the African condition” (p130), while the seventh chapter is devoted to examining his last novel Anthills of the Savannah, which tackles military dictatorship and authoritarianism. Although the setting of the book takes place under a military dictatorship, it does not according to Falola, presuppose that only military governments can be dictatorial as “There are instances of civilian democratic rules that tends to be as ruthless as those of military regimes.” (p177). There is a surfeit of examples on the continent from Malawi to Uganda etc.

Chapter eight titled ‘The sad tale of a country at war: There was a country’, which deals with what has come to be regarded by some critics as Achebe’s most controversial book, examines the writer’s memoir about the country’s civil war (1967-70). This unfortunate part of the country history still continues to rear its ugly head. For instance, as this review was being written, the news came that Nnamdi Kanu the leader of the outlawed Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) has had his trial adjourned indefinitely by the court.

This raises the issue of how the South East is perceived or thought to be treated in the country and as Falola writes, “Achebe’s There was a Country, is a narration of two countries: Biafra was a country of new hopes for the Easterners, but it came to an end at the end of the war, and Nigeria is only an idea that does not truly manifest its anthem of peace and unity.” (p202). The question of whether if the country (Biafra) had survived would have been better than what is now, is another matter entirely. Man lives on dreams. But hope is eternal.

In dealing with the writer’s other works, such as short stories, poems and essays, Falola brings to bear his forte as a historian of note to help readers gain new insights into the rich oeuvre of Achebe as history. In concluding this enriching addition to the examination of one Africa’s greatest intellectual thinker and writer, he writes about There was a Country, which he aptly calls a ‘farewell memoir’ as a “legacy book that hopes Nigeria will learn from the use and propositions prescribed in the memoir as template for curing an ailing nation… Achebe’s legacy cannot be contained in one book…, they can only be written in volumes.” (p283-4). But is the country moving in that direction? Hmm.

Falola who co-authored another book Wole Soyinka: Literature, Activism, and African Transformation (2022) with Bola Dauda, has once again demonstrated his interdisciplinary excellence with this book. If you must fully understand Achebe, read widely, don’t stand in a place or read only one critic!