By Toyin Falola

Ten years ago, Professors Malami Buba and Nuhu Yaqub gave me the opportunity to give the Keynote Address at the First International Conference, Sokoto State University, held from August 19th to 21st, 2014. The list of dignitaries was impressive, including former President Shehu Shagari, the Sultan of Sokoto, the State Governor, and the Commissioner of Education. My focus was on peace and national integration, and I chose to connect them to the broader terrain of the humanities. I want to use the opportunity of yet another return to Sokoto to revisit this lecture.

The African continent, especially after its contact with the Western world, has been the theatre of the expressions of various political, economic, social, and cultural experiments—including those imposed on it by our erstwhile overlords while seeking their own benefit, and the others we have adopted in pursuit of Western idealized notions of civilization, modernity, and development. Markedly however, neither the colonially imposed “civilization” policies nor other borrowed ideas of modernization and development have translated to political stability, cultural affirmation, and economic prosperity; the end of poverty, de-industrialization, capital flight and brain drain in Africa. What we have witnessed instead is growing economic inequalities, the prioritization of privatization over public welfare, recolonization, political repression, cultural promiscuity, widespread insecurity, and political instability.

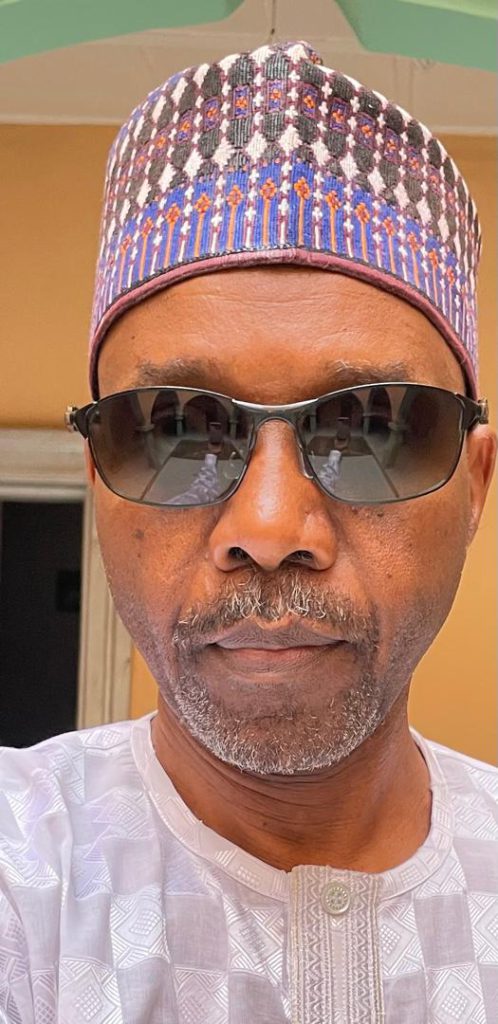

Prof Malami Buba

It was my view that Africa’s apparent development impasse, as well as the other myriad social and political challenges it faces, can be resolved by making proper adjustments to its knowledge production and utilization processes. This was the subject of my keynote address delivered at the First International Conference and Centenary Commemoration of the Sokoto State University in 2014. In that Address, which I titled the “Sokoto Manifesto,” I emphasized the role of the Humanities in promoting peace and national integration in Africa. I also clarified that the success of such an endeavour was dependent on the repositioning of the Humanities in Africa, which I noted were already beset by several structural and societal challenges.

The challenges facing Africa today are not very different from those it faced say two or even six decades ago. In fact, what we have witnessed in most cases is a deepening and/or progression in severity of age-old challenges—poverty and underdevelopment—owing to the failure of ideas and institutions to achieve set goals/agendas that would have pre-empted today’s crisis. Also, the common knowledge that Africa possesses enough human and material resource to pull itself out of the uninspiring position it now occupies, but yet appears unable to, confirms my speculations that Africa’s development problem lies not in the lack of any material or manpower requirements but in the failure to mobilize these resources for the benefit of a greater number of people and not the small number of elites who continue to steal the show. And this is where the Humanities come in.

As tools for engaging the challenges of (under)development, the humanities offer great potentials for the formulation of ideas capable of uniting Africa’s visions and energies towards liberation from poverty, underdevelopment, and every form of political, economic, and cultural (intellectual) dependence. When it was presented about a decade ago (in 2014), the “Sokoto Manifesto” identified the importance of the humanities to Africa’s social, economic, and political recovery. It was a call for the humanities to “respond to the challenge of reformulating ideas, images, narratives and frameworks” which would enable them to serve the interest of the majority as against that of a small (elite) minority. It also identified certain ‘‘powerful’’ challenges which, if overcome, will enable the humanities to win the trust of the grassroot while also demonstrating their worth to the state.

Parental, social and state persecution are some of the (social) challenges which were identified as standing in the way of the effectiveness of the humanities as tools for dealing with the limitations of development. At the parental level, the humanities, the paper explains, have been treated as subordinate to other ‘scientific’ and technological disciplines which are considered financially more rewarding and as such have enjoyed the most patronage at the home front. Socially, the more society organized its values around wealth and means, the further the humanities recede in social rankings, especially as its value is not so easily translated in monetary terms. In its interaction with the state, the humanities have been most affected by the former’s quest for easy and quick outcomes which relegates the humanities to an expendable resource that enjoys less and less state support. When all of these is viewed alongside other internal structural challenges—which include issues of limited scope, intellectual conformity, lack of interdisciplinary cooperation, and the quest for individual aggrandisement—we can appreciate more how the humanities have come to be disconnected from and undervalued by society.

Thus, the first step in preparing (rethinking) the humanities for the important task of nation-building lies in fixing its internal\structural deficiencies. In this regard, it is crucial for the humanities to deal with issues such as: of outdated books and curricula, diminishing morale, inadequate funding, rigidity amongst disciplines and educational organizations, and a high tendency for intellectual conformity (dissidence). All of these are important for restructuring the humanities and restoring some confidence in their capacity, especially given that some practitioners have, in the twentieth century, attempted to justify one-party authoritarianism and have advanced arguments for military dictatorship and other corrupt state apparatus.

The continued marginalization of the humanities was linked to the failure of society to make the connection between the management of a nation and the production of knowledge and organization of knowledge sites. It therefore behoves the humanities “to educate society on the imminent dangers of compromising the humanities, to expose and argue the logic and establish the connections of the disciplines to development so that family, society, and state can visibly see they risk self-destruction.” For an illustration, it is noted that the humanities are equipped to trace the impacts of Western global economic expansions on nations and citizens in Africa; how the political and economic projects of the state are connected to larger trends of globalization. Without such exposure citizens are reduced to entertaining false hopes in their individual capacities to self-transform and overcome the crippling structures and institutions of their society.

There are also other identified areas where the humanities can apply themselves effectively and demonstrate their worth to society. These included an unravelling of the processes and consequence of globalization and western domination on African nations and their populations, becoming the voice for Africa to articulate its protests, establishing useful cross-border ties and anthropologizing the West. The humanities can also lead themselves from combatting the excesses of modernity and western capitalism using a pragmatic appeal.

I still maintain today, as held about ten years ago in the “Sokoto Manifesto,” that the humanities are Africa’s best chance at charting a viable course out of its post-colonial social, economic and political predicaments. This position is reinforced by the fact that the same issues of poverty, underdevelopment, capital flight and western economic domination which describe the threat to Africa’s well-being a decade ago are still relevant now. The solutions prescribed in the “Sokoto Manifesto” are as relevant now, if not more so, than they were ten years ago. Today even the favoured disciplines (sciences and technology) are losing patronage to get-rich-quick schemes which question the sense in committing decades to an education that cannot guarantee a comfortable future.

Sokoto, can you lead us?