Family background and social upbringing

(Unedited transcript)

By Toyin Falola

Tell me, who is Paul Tiyambe Zeleza?

First, let me begin by thanking you, Toyin, for the honor and opportunity to do this interview with you. In the African intellectual community, both on the continent and in the diaspora, we admire and appreciate the amazing work you have done to promote African scholarship through your own prodigious publication record, but also for your exemplary support and celebration of African scholars including providing publishing outlets and mentoring for younger scholars.

Like everyone else, my personal, professional, and social identities are both multiple and always in a state of becoming. None of us is ever one thing, frozen in a permanent state of being. On the personal front, in my six decades of life I’ve been a son, sibling, husband, father, uncle, friend and colleague, and so on, affiliations that have given me immeasurable emotional and psychological sustenance. Professionally, I’ve been a student, teacher, scholar, public intellectual, creative writer, university administrator, and member of various boards, all immensely rich and diverse experiences that have shaped my intellectual passions, proclivities, and perspectives.

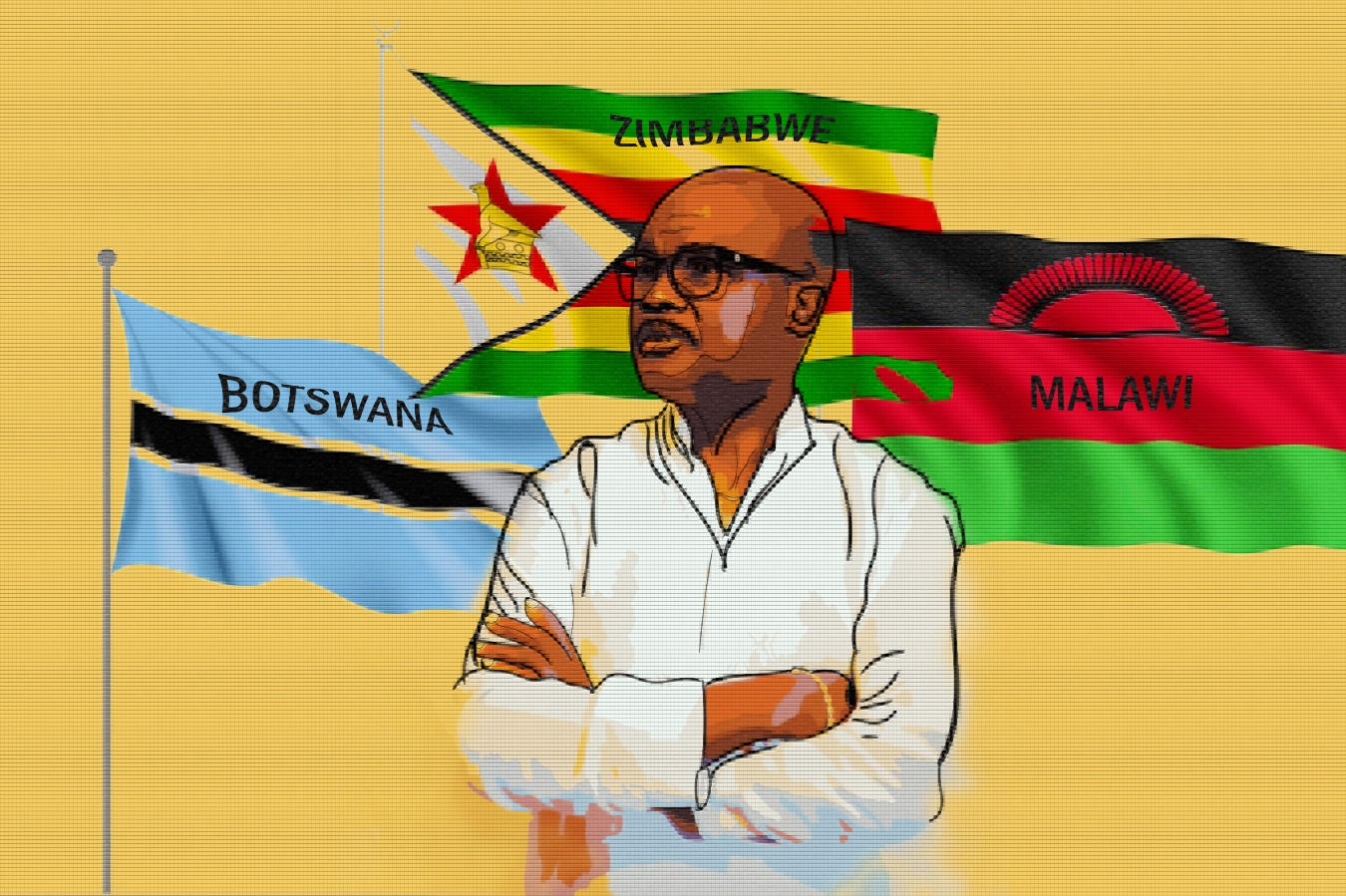

My social biography has been framed by various historical geographies. The family I was born into has lived in three Southern African countries: Malawi, Zimbabwe, and Botswana. My parents met in Zimbabwe and I was born in Harare, then they returned to Malawi where I grew up. My mother partly grew up in Zambia. In the early 1970s the family returned to Zimbabwe, while I remained at school in Malawi. Then in the early 1980s the family moved to Botswana. So my siblings and I were born in three different countries. We’re a transnational family, a multilingual and multicultural family. We’re a product of the migrant labor system of Southern Africa engendered by settler colonial capitalism in the region.

My own itinerary built on these transnational trails. I did my primary and secondary schooling and undergraduate education in Malawi. I left for graduate school in 1977, first for the University of London for my masters degree, then for my doctoral degree at Dalhousie University in Canada. My working life started at the University of Malawi where I served as a teaching assistant soon after graduation in 1976. My PhD studies and academic career took me to Kenya three times, Jamaica, Canada, and the United States.

On a more personal level, my two children were born in Malawi and Canada, respectively. My first wife was African Canadian, and my wife of the past 22 years is African American. So you can say, I’ve followed my parents footsteps by creating my own transnational family. As the saying goes, the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree! In short, my social biography has been marked by deep transnational and diasporic affiliations from birth. This helps explain my strong Pan-African identifications and inclinations.

I also see myself as a social activist, fervently committed to emancipatory causes ranging from struggles for gender equality, participatory democracy and active citizenship, to the construction of inclusive and sustainable developmental states and societies. The flip side is my intolerance against oppression and exploitation, human rights abuses, political persecution, marginalization and corruption, which unfortunately are rampant in our societies on the continent and in the diaspora.

Outside office work, I am an avid reader. I subscribe to dozens of newspapers and magazines from Malawi, South Africa and Kenya, and outside of the continent from the UK, Canada and the US. On vacation I love reading novels and biographies. I thoroughly enjoy watching movies and television serials from different regions and countries around the world on my iPad, which I think is one of the coolest inventions ever! One of my favorite pastimes is taking long walks, which I do every day. For more elevated pleasures, especially when traveling or visiting a city for the first time, I find going to art galleries and museums revealing of the collective imagination and history of a place. Musical performances, theater and public readings by authors of their work always uplift my spirits, so does eating out. COVID-19 has been a bane on these pleasures. I find cooking relaxing, an opportunity to indulge my culinary creativity and fantasies. I’m not particularly interested in sports, except for international tournaments during which I’m more invested in the victory of African or African diaspora players than in the actual game.

Let us talk about your town and country when you were growing up?

My earliest memories are growing up in Lilongwe, which became Malawi’s capital in 1975 replacing the old colonial capital of Zomba. The Lilongwe of the early 1960s was a relatively small city. I remember it as being very clean. We lived in a lovely neighborhood, or location as there’re called in Malawi, of neat two- or three-bedroom bungalows, with tree-lined streets. I’m the first born in my family so I was both privileged and subject to strict discipline. My father was a foreman, a kind of manager, in the city’s Public Works Department. My mother stayed at home and was quite entrepreneurial. She made and sold embroidery.

My parents came from two different ethnic groups, and as I noted earlier they partly grew up in the neighboring countries, so they were quite worldly in that sense. One result is that we did not grow up thinking in ethnic terms. We embraced a kind of pan-national and pan-regional identity. My mother’s ethnic group, the Ngoni, trace their history to the great migrations in Southern Africa in the 19th century spawned by the formation of the Zulu nation. My father’s ethnic group, the Chewa, trace their origins to migrations from the DRC many centuries earlier.

Both communities are matrilineal in which lineage, property, and land rights are traced through women. Colonialism overlaid its patriarchal structures, practices, and ideologies on the society, but critical elements of matrilineal culture persisted. In our family, we grew up prioritizing relatives from my mother’s family over those from my father’s. In fact, while I’ve visited my mother’s ancestral homeland many times, I’ve been to my father’s only twice. The first time was in 1960. I remember we drove all day in his green land-rover to get there. The second was in 2014 when I went with him to visit his relatives after he had returned from Botswana where he had lived for thirty years and during which he took Botswana citizenship. It’s a region of stunning beauty, with rolling green hills, golden grassland valleys, and shimmering rivers.

I started my education at Lilongwe Government Primary School from the time I was 5 years old as there were no kindergartens at that time. I initially hated school, especially standing in line during assembly, and the teachers forcing us to repeat the alphabet and counting numbers, which I found easy to grasp. Eventually, I loved it especially once I could read stories in both Chichewa and English. I was excited and intrigued by the way reading transported me in my imagination to different worlds and places, people’s lives and experiences. Thus began my lifelong passion for voracious reading.

At the beginning of 1964, we moved to Malawi’s commercial capital city of Blantyre, named after the birthplace of the Scottish British explorer, David Livingstone. Malawi’s founding president was an irredeemable Anglophile and loved Scotland where he did some of his medical studies at the University of Edinburgh, so his government never countenanced changing the city’s name. Malawi got its independence from Britain on July 6, 1964. On the eve of independence, we stayed up late, the first time I ever remember doing so. We lived within a few miles from the national stadium. At midnight, the night boomed and cracked with magnificent showers of fireworks I had never seen before. My parents embraced and danced, the only time I witnessed that public display of pure parental joy.

At that time, Blantyre was much larger and more cosmopolitan than Lilongwe. Besides, the indigenous Africans, it had a sizable population of Malawians of Asian origin, who dominated the commercial sector, and European settlers who run the few manufacturing enterprises and transnational businesses, as well as the large tea estates in the surrounding districts. Unlike Lilongwe, which is relatively flat, Blantyre’s physical landscape is made up of undulating hills and mountains.

We settled in a newly constructed neighborhood of beautiful bungalows. The area became known as the “New Lines” to distinguish it from the much older nearby colonial neighborhoods. I spent some of my happiest years there. At first, my brothers and I were enrolled at a Catholic primary school where I did my Standard 4 and 5. For Standard 6-8 I was enrolled at a school closer to our home, Chitawira Primary School. By then, I loved school. I particularly liked mathematics, the sciences, history and geography. I couldn’t care less about English, Chichewa, or physical education, which I was not good at.

At Chitawira I usually came in third in my class, behind two extremely brilliant girls, both named Rosemary. I have always wondered what happened to them, for when I went to college years later they were not there. In 1968, I sat for the primary school leaving certificate. The top performing students were selected for boarding secondary schools, and others went to day schools. The list was published in the newspaper to the great pride of my family. I was selected to go to St. Patrick’s Secondary School. All our teachers except two, the Chichewa and physical education instructors, were Catholic fathers and brothers from the Netherlands. They were demanding and exceptional. They expected and wanted us to excel. I remember the headmaster, Bro. Aloysius, telling me I was bright enough to become not just a teacher but a university professor one day!

The University of Malawi was opened in 1965 when I was in Standard 5. As it so happened, some of the new students used to walk from their hostels in one part of town to the Polytechnic, one of the constituent colleges of the university, close to our house. That’s when I knew there was such a thing as university. They looked both strange and resplendent in their black gowns which they wore everyday. I told my mother I would go to university one day like the students I saw.

I was very close to my mother. As the first born, she entrusted me with looking after my younger siblings. She taught me to cook and do household chores including ironing and taking care of the garden by the house. We talked all the time and she would usually defend me when my father wanted to discipline me if I had done something wrong or if my siblings had done something wrong. As I grew older, my mother would send me to the grocery store, or we would go together to the city market on Saturdays. That was usually the highlight of my week. Later when I got married, my wife noted I was pretty domesticated, that I enjoyed going to the store and cooking. Besides my mother’s company, I loved lingering around when she had friends over, surreptitiously listening to their conversations. When the late Professor David Rubadiri first read the draft of my novel, Smoldering Charcoal, he observed that the dialogue among the women had a remarkable authenticity and flow.

As city dwellers, we were often visited by my mother’s and father’s relatives from the rural areas. My parents were also generous in that they raised some of their nephews and nieces as members of our family. My siblings and I particularly enjoyed the company of my mother’s relatives, especially her brothers and sisters and her mother. Grandmother was a bundle of joy who enjoyed indulging us and annoying my mother for her tolerance of our occasional cheekiness. Agogo, the term for grandma, was a remarkable woman, who spent years in neighboring countries including Zimbabwe where she went with her first husband, my mother’s father in the early 1950s. She didn’t suffer fools and married three times. My grandfather established a laundry business in Harare, which apparently did well. There’s a family picture of my mother holding me when I was three days old with my grandfather in his three-piece suit.

The only time we left Blantyre was to either go to Zimbabwe for holiday or to my mother’s ancestral home village, where some of her cousins, aunts and uncles still lived. I loved visiting my mother’s relatives especially her grandfather and grandmother, who we used to call Bambo Nkulu and Mai Nkulu. Bambo Nkulu, whose real name was Ishmael Mwale, was one of the first Malawians to get a colonial education. He would regale us, his great grandchildren, with stories from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In the 1920s, he was a member of a five-man team that translated the Bible from English to Chichewa. He served as a court clerk and one of the main advisors of the Inkosi ya Makosi Gomani II, the paramount chief of the Ngoni.

To my eternal regret, he passed away in 1972, a few weeks before I went to university. I would have loved to have talked to him as a budding historian. Unfortunately, I never met my grandparents on my father’s side as they passed away before I was born. My grandfather worked in the traditional court in his district and his death forced my father, who had been a leading student, coming on top nationally in primary school national exams he sat before his father’s death, to drop out of school and trek to Southern Rhodesia.

Growing up in Blantyre in the 1960s was full of opportunities. We lived near a sports center run by the Lions Club where my friends and I often went to play lawn tennis and football, although I never really excelled in either game. We also played football in makeshift pitches in our neighborhood, as well as many other games. One of my fondest memories was playing in the national stadium for the under—11s as curtain raisers for a regular football tournament.

We also lived within walking distance to the city’s leading public library and information center, which has since been converted into a conference center, where my friends and I would frequent to read books and comics. Sometimes, we would go to the nearby hills and pick wild fruits including mangoes and guavas. One of the central scenes in my novel is of a kid falling from a mango tree and the chain of events that unfolds from that tragic incident. We made our own toys and competed fiercely in making them from cars, trucks, and buses, to guns, bows and arrows.

One particularly fun hobby my friends and I relished was making song books, that is, writing down the lyrics of popular songs. Our musical tastes were eclectic from soul music, to rock and roll, to pop music. We were particularly enraptured by the Motown sound. For African music, we mostly listened to South African bands and singers, both male and female, and famous musicians from Zimbabwe and Zambia. The local music scene was largely confined to traditional music, which we associated with the rural areas and the dances at political rallies that we didn’t much care for.

In 1968, I left home in Blantyre for boarding secondary school. I was 13. Although the school was not too far away, that was the last time I lived with my parents except for the holidays. Boarding school forces one to grow up quickly, to learn to fend for oneself, to become independent. It can be hard, emotionally draining, of course. It was especially challenging for the boys from far away and the rural areas. I loved secondary school because it expanded my intellectual horizons. I also got to appreciate more keenly the country’s diversity in terms of class, ethnicity, and religion.

I had grown up in a religious home. More accurately, my father was very religious. My mother was not. I found solace in my mother’s indifference to religion. My father would have us do Bible study several times a week. While I liked the Bible stories, I found the studies a chore and I rebelled by not going to church. When my father’s denomination, Jehovah’s Witnesses, was proscribed by the government in 1967, I was secretly pleased.

But when the government started actively persecuting members of the denomination, I was alarmed. In 1972, fearful for his life and that of his family the family fled to Zimbabwe. I declined to go with them and chose to go to university where I had just been selected whatever the consequences. I was not going to sacrifice for a religion I didn’t believe in, but I was prepared to do so for higher education that I so desperately aspired to have. It was one of the hardest decisions of my life. I was 17 years old. My parents were fearful for me. But I am glad I made that momentous decision.

PART B

INTERVIEW ANALYSIS AND REFLECTIONS

BY TOYIN FALOLA

ZELEZA AND THE ROOTS OF SOCIO-CULTURAL PHILOSOPHY

Humans are generally entangled with a web of identity not because they are naturally inclined to multiple indexes of identification, but centrally because they find themselves in an environment configured to align with plural ethnicities and nationalities. A being does not drop from the sky like a wandering alien; instead, we are attached to a family group that comfortably forms a unit in every human society. Farther from this, we are groomed by individuals who are often entirely unrelated to our sociocultural backgrounds. Because of the lived experience with a different set of people, we are once again accorded another identity within which we would function and with whom we would find in-group sustenance. As we grow up, we navigate our ways in human society to attain a different level away from the cultural, professional, political, economic, and philosophical, and we become affiliated with multiple or diverse identities, which make it generally difficult for us to be confined to a single form of identification. Ultimately, this is the condition that we all find ourselves.

A conversation with Paul Zeleza further confirms the assumption that human nature is transcendental and unfixed. We choose identity either consciously (perhaps after one can make decisions when attaining a certain age) or unconsciously during our development. Zeleza’s trajectory of identity formation is unquestionably eclectic, for he has evolved through the years of being associated with, or by deliberately associating himself to, some well-defined societies of people in professional and practical worlds. Being a son, a brother, an uncle, a husband, a father, and more importantly, a friend have all shaped his perceptions and responsibilities to the society that groomed him. As a son, he learned that one’s responsibility as a social animal is not exclusive to an individual, especially in a continent of people with a deep-seated interest in its human interrelationships. A child’s responsibility to his/her parents and later siblings, for a start, is socially given, for they are part of the materials that form the network of human connections used mainly to advance the social courses of actions. As such, a child considers him/herself an asset and also an instrument: An asset because he/she would automatically inherit the responsibility of advancing the collective ambitions and goals of his/her immediate society (which may not necessarily be defined culturally), and an instrument because he/she is a tool for shaping the said society. In other words, there would be no such notion as social evolution when there are no individuals who would bring about this supposed change. The situation of Zeleza is evident of this, such as others do in similar capacities.

The uniqueness of his situation is confirmed by the historical geographies that nature has associated him with in good measure. To take as an illustration, his coincidence of being birthed in Zimbabwe, raised in Malawi, and having a professional relationship with Botswana all combine to produce the intellectually eclectic individual we have in him. By this permutation, he has experienced a magnificent interplay of cultural diversity, social interactions, and philosophical eclecticism. In fact, anyone who would be prepared for important things in life would necessarily have the opportunity to test different sociocultural and sociopolitical human conditions. It provides one with the required human capital to successfully manage people and advance their collective dreams. Therefore, while it was possible that the childhood and experience of Zeleza would have been dismissively adjudged as complex, or maybe more plainly intricate, nature has carefully been preparing him ahead for the vast responsibility that would be attached to his personal, social, political, and professional identity. We cannot contend that this transnational mobility, known to Zeleza and his family, provided them with the needed technical and philosophical knowledge about Africa, and the complex political terrain enabled by the expediency of colonialism. He had his primary education in Malawi, giving him the necessary sociopolitical exposure to situations and circumstances of the postcolonial time that defined the African children within the context of that timeframe.

Meanwhile, human sociocultural philosophy is always in a constant state of flux. And due to this mobility and/or flexibility, we are able to imbibe a culture of eclecticism in our personal and professional lives. Without being eclectic, or if you like diverse, appropriating the right kinds of human philosophy to solve an existential challenge of a globalist posture is readily difficult, for the approaches needed to address one’s social issues cannot be used when confronted by intricate situations in culturally distant places. At the same time, the situation cannot be evaded in a world in which physical and geographical boundaries are collapsed through the internet―a generational project meant to enhance a globalization agenda. When Zeleza again advanced his academic pursuit to London in 1977, he was preparing for something massive and transcendental. As if he had an incurable urge for the acquisition of knowledge from very diverse sociocultural environments, his Ph.D. academic experience took him to continents, including but not limited to the Americas and Africa. For anyone who understands the tradition in the academic community, it would be difficult not to understand that any academic expedition that takes people from one cultural end to another would always have the advantage of exposing them to different human cultures. For Zeleza, all these became a force that determined his transnational mobility and constantly mobile identity.

Therefore, it is not suspicious that a man exposed to this level of human condition and experiences would be essentially Pan-African or inclined to accept his own complex identity. As a child growing up, his intra-continental mobility has been a product of postcolonial politics that continues to enhance Africans’ spatial mobility and render them in a continued state of flux. As an academic, he was exposed to the educational trajectory of the continent, how it has been colored, and how it has been systematically affected by the said experiences. Being exposed to the network of intercontinental industrial and political expansion ignited a revolutionary drive in him, which later transformed into his series of aspirations and focus on African epistemology. Serving at the professional and leadership level was a protest and resistance culture to effect changes in systems that are essentially rigid due to their dependency on colonial systems and structures. Whereas it is not only important to be flexible if one wants to compete in current global socio-economic engagements, especially in the form of education given to the people, the need to develop an eclectic sociocultural philosophy cannot be underestimated as these are needed for the enhancement of one’s civilization agenda. Compared to other civilizations, Africa is lagging for reasons that are not unconnected to their limitations of educative initiatives.

In the intellectual category in which Zeleza found himself, it is impossible not to become a revolutionary tool, providing people with the most basic understanding of their cultural and political situations to provoke in them the revolutionary thinking needed for sustainable evolution and development. By becoming a gender equality advocate, for example, shows that he has mastered the situation of the continent and realized that one of the clogs in the wheel of African development is their rigidity to gender roles. Although people are usually of the opinion that Africa is an extremely patriarchal society, an assumption that is more controversial than truthful, it cannot be disregarded that the patriarchal conditions were aggravated by the political schematics of the colonizing force. Within the spate of a little less than three centuries, Africans, having been well exposed to the systematic and systemic culture of patriarchy, have perfected the act of excluding their female counterparts in public administration and other political engagements, disempowering them and making them a dangling appendage to their male counterparts. This has brought some unmitigated disaster for Africans and their culture on many grounds.

For one, the exclusion of a female demographic in an environment where they are socially expected to function at a maximum comes with some unforeseen consequences. In addition to their roles as caregivers and mothers, women are expected to be the shock absorbers of the family. They are socially expected to combine caregiving with teaching the children. They are constantly pressured to support their husbands (whatever that means), and other roles are culturally allocated to them. This is despite the fact that the economic opportunities needed to function at maximum in these responsibilities are not usually allotted to them. This compounds their woes and forces many of them to become essentially vociferous advocates of gender equality, in cases where most of them are not depressed already. For anyone who is informed about their existential challenges, it is helpful rather than shortsighted to join the bandwagon of their protest in the quest for a better society. The fight does not necessarily need to be gender-specific. Anyone and everyone who sees the socio-economic lopsidedness is morally expected to join the campaign for gender equity because whoever is fighting for gender equality is seeking the betterment of the society. Perhaps, this is what informed Zeleza’s inclusion in the gender equality protest, whose waves and tides have been definitely registered in the minds of people in this contemporary time. For the continent to progress as expected, the unassigned workload that the male demographic has assigned for themselves must be shared with their female counterparts to relieve them and encourage alternative thinking and approaches in sociopolitical problem-solving.

It is evident that anyone who supports the above agenda would accept a participatory democracy where individuals are represented and included in their social development. Democracy, which is an often-preferred political system in contemporary times, remains the most transparent system for the promotion of a nation and its socio-economic condition. However, the failure to befriend an inclusive government would always have adverse effects observable in African politics that have overtaken the continent in recent times. Having preferences for the exclusion of the people in any governmental dispensation breeds political patronage and a clientelistic government in which institutions are disrespected and abused by those in power. Africa comes unclean in this aspect. One of the reasons for the emasculation of their economic system is that participatory politics has been supplanted in preference for exclusionary ones. Thus, the resources with which the continent has been blessed benefit only the bureaucratic arrangements in the continent. The ordinary people are powerless, perhaps because administrators have found a consummate method of excluding them and their voices in the realm of making important decisions. In essence, the experiences that shaped Zeleza’s sociocultural philosophy are the ones that he grew up to challenge and change so that succeeding generations would not face the same problems that he witnessed.

It is often said that a good reader is a good leader. This saying did not come from the simplistic association of readership to scholarship, by the way. It is from the understanding that on the pages of books are silent ideas and philosophies carefully and artfully archived by brilliant authors whose communication with the audience spans beyond fixed generations. The ideas in books, when unearthed as archaeologists unearth evidence from forgotten sites of history, are in themselves powerful and not without their forces of creation. They create the energy to consider events from a different perspective and challenge traditional models of thinking. Through books, humans are open to diverse discussions and ideas that reflect different sociocultural or sociopolitical conditions. By their appropriation, therefore, it is likely that they would be useful for the enhancement of a revolutionary trajectory to move the people towards a better and more desired condition. Unsurprisingly, the fact that Zeleza has been an avid reader is a revelation of his intellectual ingenuity. Raised in a generation where all hope on the African future is cast on the fact of quality education acquisition, Zeleza has constructed for himself a solid intellectual identity that has unarguably molded him into a respectful and respected individual. While formative education is usually determined by parental and sometimes social factors, the education in subsequent years is usually exclusive to an individual decision.

Despite the freedom that comes from adulthood, however, one’s disposition to life is shaped by the cultural traditions and experiences that one has as a child. In an African environment, the fact that individuals are exposed to a strong social upbringing further solidifies the cultural tradition identified here. Parental contributions to the socialization of children take crucial precedence in the African society, for they are not only the shoulders upon which a child stands to see the world, but they are also the eyes with which they see the social configurations entrenched in the people’s philosophy. Zeleza has good parents who were consciously available for him to have a fulfilled relationship with the environment. Having a father who provides for the family’s financial needs and a mother who supplies the family’s moral and ideological oxygen is an added advantage to him as a child. It was more soothing for him because he was the first child of the family. By that virtue, he met the full preparedness of parents who provided all the needed support for his development. The fluidity of ethnic identity that was well celebrated among Africans before the ascension of the visitors helped him in the visualization of the society, not from a jaundiced perspective, but rather from an elaborate one. He already was equipped with the knowledge that the society is diverse, so it helped him see himself as the center of anything and everything, and shaped him to consider himself a part of the moving society whose knowledge and contributions are hugely important. Indeed, it was because his childhood experience followed this trajectory that he sees himself as constantly evolving and not frozen in a permanent state of being.

Thus, Zeleza’s brilliance was nothing short of conscious training, dedication, determination, and strengthened commitment, all of which were accumulated from the beginning of his childhood. Enhanced by his purposeful parents, he was married to books and numerous scholarly production from a very young age. This earned him the admiration of many and also placed him in a desirable and appropriate level because he was poised and ready for the challenges of life. Even when the indigenous educational systems of Africans were submerged and supplanted by the hegemonic civilization, its structures still survived in a more sophisticated manner in contemporary times. For example, it is within the educational process of Africans that children learn about the immense responsibility ahead of them, and the social contributions they are expected to offer to make it better collectively. Without this, it would be next to difficult for them to understand their roles as members of the society. Perhaps, it comes from the knowledge that the colonial adventurers would not tell them; the knowledge that Africans are socially expected to perform some tasks is passed through the parents, the primary agent of socialization and education for the children.

Being brought up by responsible parents helped Zeleza beyond expectations. He was shown unmixed parental affection and love. Through his parents, he learned that he has a responsibility to the basic family that produced him. Although such knowledge prepared him for the bigger one in the future, the fact that he has to cater to his siblings was injected into him right from the beginning. And this underscores, once again, the place of the African woman in the structuration of the African society. On the occasion that they are abandoned, the results in most cases are usually devastating. Zeleza was schooled by his mother from childhood so that the siblings, the younger ones behind him, would bring social pressure on him because, by the configuration of human relationship, kinship makes it important that he provides for them, not necessarily in terms of money but in the idea that they should benefit from his comparative advantage because of his age. The pressure to support the siblings is not exclusive to Zeleza, and it is not because he is a male. Rather, it came because he was the first child of the family who had the opportunity to experience parental attention in bringing him up. The first child takes on additional responsibilities.

In essence, the sociocultural philosophy of Zeleza is a mix of varieties of childhood experiences. His being raised in a postcolonial environment brought out in him the determination to make a difference by giving full attention to the needed sociopolitical and socioreligious changes. He was also shaped by the politics of an African household where he was introduced to a network of social activities. The fact that the colonial educational system failed to create in him contradictions that reflect instability further affirms the assumption that he grew under the right parents. He moved from place to place because of factors that were not unconnected to postcolonial political eventualities. He is very refined because he grew up witnessing cosmopolitan. Because of divergent opportunities, he has continuously evolved, advanced, and achieved a height that shows that he is dedicated and focused. Personally, professionally, and socially, his identities are constantly shaped and reshaped by events and circumstances, and the inevitable political activities that serve as the context.