THE PAST TOWARDS THE FUTURE

By Toyin Falola

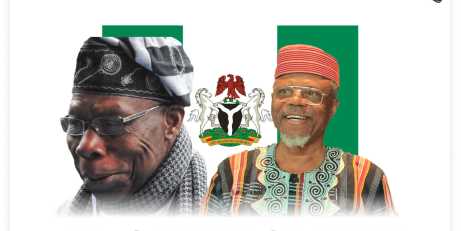

(This is a report on the interview conducted with President Obasanjo on Jan. 31, 2021) For its entire recording, see https://youtu.be/8_ue5Hvi1vY)

Obasanjo as Head of State

Obasanjo as Head of State

In global politics, not only is the situation in Africa a common topic of debate among experts in political science and historical scholarship, but their near precarious conditions recently have also been a subject of worry and genuine concern to stakeholders and leaders within the continent. More perniciously is the question of inherited controversy and catastrophic socioeconomic and cultural conditions that their colonial imperialists bequeathed to them. The experience of colonialism has not only continued to haunt them; it is the gamut of their political complications as different African countries are entangled in the complex web of post-colonial estrangement. However, it is noteworthy that Nigeria is a cornerstone of the continent in the context of its efforts and contributions to the displacement of the strange Europeans that have forcefully overtaken its economic and political affairs. The enhancement of peace in the heydays of independence in Africa, which became the sensation needed for the indigenization of the inherited political system, and the construction of the African identity were calculated to bring them to their promise land. But the euphoria of efficient activism and the guiding light, which Nigeria served as for the African countries, became inundated with challenges. It slacked and suffered the pangs of political misadventures that extensively enervated them.

Obj on his PhD graduation day

Obj on his PhD graduation day

In almost seventy years of Nigeria’s independence, the country has seen various politically combustive and economically convulsive experiences that, either at a point, threatened their unity and commonality of their purpose or hurt their togetherness so much that it sacrificed the once-promising relationship which they have been forced to build by the shared experience of slavery and then colonialism. To be candid, even someone who was conceded to be arguably one of the most successful, impactful, and efficient Nigerian politicians alive, the erstwhile President Olusegun Obasanjo, in the recent series of The Toyin Falola Interviews agrees that Nigeria has suffered from internal contradictions and ravaging conflicts that have racial and ethnic coloration―a deep scar that remains difficult to mend. And because of the deep-seated pains, most of which are psychologically internalized and concealed, the underbelly of the country’s political structure is witnessing an accelerating decadence. Of course, with the hindsight of a 30-month civil war and sporadic genocidal insurgencies, we are all aware that the consequences of such relationships could be fatal, deadly, and more insidiously, poisonous. Nothing can vividly explain the country’s political bond’s superficiality than their stratification whenever national concerns are up for debate. It became especially more pronounced from about the last five years.

Perhaps one thing which could serve as a consolation or that could douse our possible despair is that the incidence of mutual distrust and political betrayal is ubiquitous, most notably with our recent global experience at the political domains. The great United States was embroiled in the undignifying political escapades of their politically dislocated prodigal adult, who became much glued to power and suddenly could not reconcile with the situation of not having it for another four years. The almighty European countries are also not excused from the global miasma of intricacies and controversies, the successful pullout of Britain from the European Union, and the different reactions of various others that challenge their democracies. China became a moral outcast, of course, because of its roles in the generation of a virus that is reshaping not only our politics in the global community but also determining how economically we can continue. African countries sometimes succor to realizing that political, economic, and social challenges are not particular to or patented for Africans. And in fact, they came up with a thick skin for public resistance, believing that there is no single country in the world that is not immersed in consuming trials. Africa is an expression of global politics, and its position and travails are considered in the recent interview. More importantly, contemporary Nigerian politics is discussed.

Obj in Aso Rock

Obj in Aso Rock

When asked by Dare Babarinsa if Africa is growing, Olusegun Obasanjo took the question head on by discussing the circumstances around the continent’s situation, which can be seen as not independent of the colonial adventures in Africa. He responded that one notorious problem that continues to ridicule the political efforts made even by the nationalist Africans in the wake of independence is the artificiality of the colonial borders. He mentioned that while we cannot prevent the action of colonialism and the attendant imperialist orientations, we appear to be eternally helpless in the fabrication of a geographical identity that would be practical for development. Without struggling, what the democratically elected Nigerian President between 1999-2007 hinted at was the suffocation of economic relations among these various African countries that inevitably accompany the structured borders. The British African colony is at political variance with the French-captured environment. Portuguese colonial Africa would not be in sync with the German colonialist settlements because they are exploited differently and in a manner that the contiguous colonial lords could not check. All these happened irrespective of the fact that these divided African peoples perhaps share a common linguistic ancestry. From the politics of difference and segregation, they created an inexistent psychological space that became wider and wider as they got deeper into politics. If anyone wants to understand this, they should reflect on the near impossibility of inter-economic links between these countries.

Obj at 80

Obj at 80

Political development is not rocket science. One can easily see the connection between a people’s progression in the political domain and their conscious decisions to attain the height. Once the said African countries find it principally challenging to create the needed atmosphere where economic prosperity can be germinated, there is no magic about it; their advancement would be affected. The French Togo, which considers the British Gold Coast not as people of common ancestral legacies but as strangers caused by the deliberate partitioning of the continent, knew there would be problems in jointly considering the various ways they could bring about the desired transformation for their people. Nigeria that sees the Benin Republic as a distant cousin would automatically find it challenging to facilitate mutual economic engagement, which would have measurable effects on the two sides and vice versa. In essence, there would be problems with their development as they have been conditioned to see themselves differently. This is more compounded by the fact that even the erstwhile imperialists do not, in their good conscience, want them to come to a profitable conclusion. Obviously, France is not satisfied that its ex-colonies are free and would always do anything to sabotage their political development. This is not a wild conclusion; the economic treaties made with Francophone-African countries are unequivocal in their bias against these countries. These are the highlighted reasons for the stunted growth of the African countries. However, there are some with beaming hope that many of them are circumscribed in challenges that bring this to bear.

Prof Falola, President Obasanjo, Prof Ademola Tayo, VC Babcock University and Prof Ishaq Oloyede in 2019

Prof Falola, President Obasanjo, Prof Ademola Tayo, VC Babcock University and Prof Ishaq Oloyede in 2019

Noting that the great Ebora Owu (as fondly called by admirers and critics) was linking African conditions to the experience of colonialism with the European imperialists, Professor Olajumoke Yaqob-Haliso, a panelist in the interview, immediately asked for the political understanding of Obasanjo about the unprecedented influx of Chinese into Africa as a sign of their economic exchange and queried if that does not signal another form of conscientious colonization, albeit a voluntary one. We had the opportunity to understand how African political leaders, especially those who are at least academically informed, think. Obasanjo’s response was not different from Nelson Mandela’s when asked how he felt about Fidel Castro and the supposed relationship of South Africa, and perhaps the whole of Africa, with the man despite being a sworn antagonist and unrepentant non-conformist to Western permutations and condescension. Nelson Mandela, knowing and seeing the underlying mischief in the question, quickly responded in a paraphrase that the West must come to understand that if someone is tagged an enemy of the Global North or their European counterparts, it does not automatically make them an African enemy. Friendships, and of course enmity, should never be inherited; it must be deserved. Even when Fidel Castro, the one nailed and condemned by these Western countries was conceived negatively, he was not anti-Africa in any form, and for this reason, did not deserve African enmity.

This would have given us a clue as to what Obasanjo said in response, but it got more interesting. The courageous President argued that the presence of the Chinese in Africa is an escape formula from the shackles of financial captivity, which economic dependence on a single source, such as America or Europe, has facilitated for ages. Even when the Orients, in their politics of patronizing Africans, tried to smuggle their blackmail on African conscience so that the latter would be conditioned to take a detour, they decided to consider China’s presence as a sign of potentially stunted economic growth. The fact, in a real sense, is that they were merely raising a false alarm, not because they were genuinely concerned about the financial and economic safety of Africa, but because they desired to continue their monopolistic undertaking. Obasanjo disclosed that his response to this question was informed by a recent experience he had with some of his American friends in the political sector who derisively questioned him about their “new colonizers”―the term often used to not only incense African politicians but also to paint them as unthinking lots who would eternally find it difficult to decide for themselves. In what we come to find out from his position, he not only discarded their unrequited messianic concern as pure alarmist rhetoric, he wittingly alleged them for the intrusion. He asked, sarcastically, if the same condemned Chinese figures were not compulsively present in the American economy.

We understand that Africa’s relationship with China is purely centered on economic exchange, and if the Chinese agree to do business with them, just as they do with others in Global North, the decision to accept or reject them is exclusively African. Indeed, there is the need for African leaders to be very circumspect, especially with their demands, commitment, and bilateral agreements with them because when not decisively tamed, the urge for personal riches and the greed in the bloodstream of some African leaders could be the Achilles’ heels that would bring about their unforeseen ruination. For example, the concession of some very important government properties to China to get loans or other aids from them would be extirpative and dangerous to them and their collective engagement. This means that although the African people would have intended to get out from an age-long economic quagmire, their leaders’ untamed greed would have dragged the people into the rounds of undeserved servitude after destitution. Therefore, what we deduced from the response was that economic safety, just as security and survival are central to animals in the jungle, is necessary for humans to keep their political relevance and also make themselves essential in the grand scheme of things. The fact that they have experienced a too-high level of economic desertification means that they are rendered helpless and in need of immediate financial rescue. Therefore, they must seek assistance where they believe it lies.

From an analytical angle, what Obasanjo gave as responses are intellectual exploration sites where one can come up with numerous theoretical ideas. For instance, when I asked him about when he developed a thick skin for criticism, the response he gave was phenomenal as it addressed what we have explained in the above paragraphs. Obasanjo concedes publicly that being dead to the emotional outcry of people is one of the ingredients of becoming great. Opinions are naturally as diverse as human numbers; therefore, when there is an accommodation for destructive criticism, an individual is bound to lose focus and become needlessly distracted. People would always come with a baggage of opinions, believing that their perspective is reasonably the best approach to an emerging situation. While the appropriation of several views represented by cross-examination of ideas may not always be beneficial on many occasions, that individually, many arguments could be fatalistic and dangerous when accepted makes the acceptance of criticism difficult. People see situations and positions from their own perspective, not because they are relatively objective in the actual sense, but because they have been programmed by society to see issues from that perspective. Looking at the same problems, a historian would see it differently from a zoologist; just as a linguist would most likely conceive it differently from an epidemiologist.

How, therefore, is this related to African situations? That Africa (represented by their political leaders) should develop a thick skin for the criticism and baseless accusations of the West is long overdue. In fact, the idea of listening to the West in matters concerning African survival has impeded the latter’s growth and expansion. The erstwhile colonial leaders who extracted a people economically and in human resources would be suspicious if they suddenly become empathetic to the colonized situation; mistreating a people for more than 400 years is not demonstrative of any compassion. The fact that the West is becoming quite concerned about African safety in the current time should be a real source of worry. It is either that the West is becoming increasingly concerned that its erstwhile slaves and subordinates are about to get their freedom in the real sense, or that its putative competitors, in this case, the Chinese, will have the upper hand on them if they lost Africa. These two hypothetical scenarios are not far from becoming a strong possibility. The crux of the matter is that the African people must defy the destructive criticism of anyone who questions their resolve to freedom. While it is good to entertain constructive criticism, as this would help them evaluate their political progression, taking destructive criticism could be distractive. The cost would be that their progress is sacrificed along the line.

One would marvel at the intelligence of Obasanjo, and perhaps like us, ask if the future of democracy is not under a cloud in a situation where African leaders develop a thick skin to the words of reason. This is because there is a fragile line between dismissing the accusations levied against one and being nepotistic. The underlying effect is that such a leader could potentially hide under this to wreak havoc on his people. Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, the Africa president that gagged the media entirely by shutting down social media platforms to bar external observers or criticism (either constructive or destructive ones) in their recent elections, might think he has developed a thick skin against his putative enemies; meanwhile, he was being nepotistic. Would such an approach not, therefore, mean that democracy is endangered? Here, Obasanjo yet again made an incisive elucidation. He argued that democracy is the proven best alternative that we have in the current time and that leaders’ nepotistic tendencies does not signify the weakness of the political system; it only showcases the fault of the leaders themselves. In other words, when we have pathologically ill-bred leaders in the corridor of power, they bring their problems to the system to have their ways. Still, they can only be checked by the institutions made available by democracy. A good example is the immediate past American President, Donald Trump.

Baba Iyabo, as sarcastically called ocassionaly to bring comic relief, also addressed issues of internal contradictions that happened in the Nigerian past, which brought about the much-debated civil war that lasted for 30 months between 1967 and 1970. Questions were asked by people concerning the incidence whose deep scar was reincarnated by blatant ethnic profiling that emerged with the current Nigerian President, Muhammadu Buhari, since 2015. Obasanjo admitted that such reactions were not unexpected, mainly because the President was somehow insensitive to the people with some comments he made at the beginning of his tenure. A democratically-elected president who declared his desire for sidetracking an ethnic identity is very dangerous to national development. The affected people would always activate their senses to evaluate every action taken, even when the measures were not ill conceived. There is hope for the people, regardless of whether the reign of a president, regardless of how bitter his stay, would always have its elastic period. Therefore, the resolve to rebuild the country should always be stronger than an ethnic jingoist’s desire in every respect.

Finally, the place of the youth in the development of Africa was energetically emphasized. The youth must definitely come to the continent’s rescue, but that will be at a cost. It begins with their understanding that there would not be any African leader enjoying the perks of leadership who would voluntarily vacate the position for the youth’s ascent. This is hardly found anywhere in the world. The youth must harness their energies and harmonize their thoughts to collectively challenge the geriatrics in power, who are disconnected from the contemporary realities and lack the ideas needed for its rejuvenation. They have to moobilize at the grassroots level. In the demonstration of their readiness, the world would see their genuine interest and support them for what they stand for. Although he did not mention Bobi Wine of Uganda, who challenged the administration of Museveni in their just-concluded elections, Obasanjo’s body language was not concealed to reveal that what he meant was replicated in Wine’s dogged character. Even when the young man was denied his mandate, he has left an impression that would be leveraged on in the country, post-Museveni period. Obasanjo encouraged the Nigerian youth to take such bold steps and make it uncomfortable for the leaders to give their mandate. They cannot do this through violence, though; it could only be achieved through their active participation in politics.