PART 3:

AYINLA: THE MAN WHO BECAME A FILM

By Toyin Falola

Omowura with the famous Olumo Rock in the background

Omowura with the famous Olumo Rock in the background

It was in one of our nocturnal phone calls, the united meetings of owls, that Tunde Kelani (TK) of Mainframe Production, a larger-than-life film director, told me that his next movie would be on Ayinla Omowura. He had previously shot down my idea of a movie on Isaac Delano’s Aiye Daiye Oyinbo, saying that it could only work as a series. As he was talking, I started to play one of Omowura’s Apala’s songs for him. Two spirits became connected.

I grew up with Ayinla’s music in the early 1970s. It was not the songs that my school mates would listen to. Far from it! It was not the one we used in college parties. Never. It was the music in local bars, the street music, the favorite of the lumpen proletariat. Thank God, oil money was already spreading, and Ayinla benefited from it, as did his contemporaries. He did not need us, and our campuses were useless to him.

The conversation with Segun Odegbami would not have been possible without Ayinla. Neither would have been the movie. His music life was impactful, his career was robust. His ending, stabbed to death with a beer bottle, was tragic. Years later, I was to speak with the heroic nurse who attempted in vain to save his life. Blood loss was in volume. Broken veins were rivulets.

Who was he? Arguably one of the most prolific Yoruba indigenous musicians that ever lived is Ayinla Omowura. Born in 1933, when the colonial architecture was reaching its peak, Ayinla was groomed in an environment where the Yoruba people’s cultural framework faced torrential challenges coming from the waves of colonialism. The formative years of the man were spent learning the rudimentary world of his people, the beauty of the culture, and their language’s fecundity. Omowura, as popularly called, was internalizing the rubrics of the colonial institutions and how the Europeans had colored the Yoruba world by their systematically defined institutions. However, Ayinla would demonstrate that he understood the politics of representing cultural identity through his continuous delivery of breathtaking cultural episteme in his Yoruba songs.

His greatness and artistry in the indigenous musical engagement are underscored by the audience he commanded and was still able to sustain even after four decades of bidding the world goodbye. There have been successions of indigenous musicians in Yoruba history, each of them coming and dying like a candlelight in a hurricane, but none of them has been able to build the cultural awareness whose foundation has been set up by the ingenuous Ayinla.

Kelani with the cast of the film

Kelani with the cast of the film

Perhaps, the posthumous recognition accorded to the man is partly because of his musical dexterity; it is not contentious, however, that his vocalist competence and industry are the two qualities that keep him in the people’s memory. Ayinla Omowura’s youthful age was characterized by various social experiences, all of which shaped his perception and resolution in life. He grew up in a heavily competitive environment where the struggle for survival was considered the gateway to relevance. Without personally making extensive and extraneous efforts for one’s life, it was difficult to change one’s social status in Nigeria. Omowura was notably successful so much that the aura of his success was felt across the coastline of West African countries, especially in places where Yoruba was their linguistic heritage. His life became exemplary because it was full of intrigues and intricacies. His success story was not one without considerable challenges. He learned very fast and could develop a wide range of ideas from the activities of his environment. Because of these characteristics, he became the people’s choice as Ayinla could easily collapse social and political issues in his music to educate the public about their political direction. He was feared by some and also admired by many. Those who considered him a threat found his fame intimidating and realized he could achieve whatever he embarked on.

Many successful persons across human history have had to encounter some challenges that became their major impediment at a point in time. The greatness in them usually does not also make them see the challenges as barricades; they consider them the necessary steps to climb in their growth course. Omowura belonged to this class of people. His youthful age was full of suspense as he was embroiled in the activities that made adulthood a worthwhile embarkation. Many people who do not go through the phase of heated competition and strive usually do not have portions of their existence to inspire suspense when their stories are rendered. Omowura experienced this.

Omowura

Omowura

Ayinla grew up in an atmosphere where feuds and acrimonies were the structural and systemic foundation of greatness. The environment is weaved in such a way that without developing the capacity to weather the storms in society, one cannot entirely be certain of any success. It brings the solid aspect of their humanity to the fore and makes them inflexible in most cases. Their rigidity, however, does not symbolize conservatism; it, however, highlights their aversion to failure or anything in the form of that. From close observation and evaluation of his songs, one cannot but marvel at the magnitude of his intellectual brilliance, demonstrated through his pragmatic ability. He was socially responsive, and his songs could provoke instant social reactions. Thus, his music continued to choose individuals who wish to improve their knowledge about society or update their moral values.

Perhaps in the whole world generally, music has always received social attention according to the degree of social controversies it could generate. In some cases, it is used as an instrument of liberation for the people by the level of an organized indictment of the political class. The controversy in this form usually attracts some political reactions especially by the representatives attacked by it. In some other cases, however, music is used to promote interpersonal frictions. The target opponent is morally expected to come back with a more compelling response directed at their identified opponents. With the escalation of these tensions, the society is entertained and have their social world beautified by the brawls between the contenders.

Anyone familiar with the songs of Ayinla would understand that he used the music as the medium of education and then confrontation. Education when he dived into the Yoruba people’s moral world to bring values that were becoming obsolete or out of fashion, perhaps because of Western civilization’s pressure. Being one affected by the colonial establishment; the Yoruba world faced these challenges in the 1960s upward. The tide of politics favored the Western method, which gave room for importing moral frameworks from the imperialist. The decision’s cultural outcome was that many Yoruba values are withering away against those that are considered morally incompatible that came from the Western world.

However, when Ayinla Omowura used the music medium as a means of confrontation, one cannot but be enthused by his exhilarating display and vocalist competence so much that one could be inheriting his acclaimed detractors, without knowing of course what the foundation or the reason for their brawl was. In Abeokuta, there were different kinds of indigenous music talents, and that there was space for anyone to reach the peak at the period, which gave room for heated competition. In a society that was fast leaning towards the Social Darwinism philosophy, growing or reaching a desirable height is directly linked to one’s ability to initiate rivalry, especially if one is a musical genius.

On many occasions, Omowura metaphorically referred to himself as a long moving vehicle, a trailer, wise speed and weight cannot be dared by light equipment. He would dare anyone to challenge him musically in his sonorous voice if they were certain of their music competence. His cameo in social events was the source of attraction, particularly to the female folks who admired his musical dexterity and appreciated his outstanding voice. It has been revealed that the recruitment of Ayinla into the Apala music band was principally because of his voice. No matter one’s inclinations to Yoruba music, as long as one understands the language, the music of Omowura was not something to starve with attention. Not before long, he became a household name, and everyone wanted to associate themselves with him, either as fans or as managers.

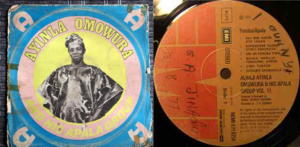

Omowura’s iconic recording tape

Omowura’s iconic recording tape

In Yoruba musical engagements, one cannot but notice that the brand of Ayinla Omowura’s song is different from what was known beforehand. In fact, he established the uniqueness of his song when he said once that “the Apala music he’s singing is a movement, and that he is the one driving the long vehicle; therefore people (his contenders obviously) should be mindful of their steps in the music scene, as he would clear them off the road if they refuse to surrender.” Being a pioneer in the system helped his music career. He found absolutely no difficulty in maneuvering his way while bound with the microphone. He would come up with creative weaving of indigenous ideas that his audience would appreciate and equally celebrate. They feel always entertained because the man’s melodious composition always sent them away from their physical worries.

Mixing educative information and lacing it with comical expressions are the two factors that canonized the music of Omowura in the hearts of the Yoruba people. His songs are seen as rooted in cultural pedagogy, and he was considered a social instructor. When he sang, there were bodies of proverbs, wise sayings, axioms and wisdom that one can extract from his songs. It was because of the probability of getting any of these that people are drawn to his music.

In Yoruba’s ontological designs, there are three phases of the human journey on the planet: the living, the dead (the ancestors), and the unborn. The first is occupied by people who are still on earth. The cultural belief is that the unseen forces usually control this people’s activities. Their unseen status notwithstanding, the Yoruba people believe that those in the second phase, the dead (the ancestors), have the spiritual qualifications to influence what happens to the living. Therefore, it means that there is a need for a medium of communication between the living and the dead so that the latter can be invoked, especially when humans want them to influence their lives in a particular direction. Among them, the Yoruba believe, there are the elders whose closeness to the second phase makes them reserve the honor of invoking the dead and also there are the groups that are occupied by those who have the spiritual capacity, and elderly women (awon eleiye) are understood to share the same power of invocation. Therefore, this means that they need to be propitiated in any human involvement to prevent their destructive actions from one’s embarkation. Ayinla Omowura understands their social and spiritual essence and therefore dedicated time to praise them in many musical performances.

If one is familiar with this cultural behavior, the lines “Igba abere l’a fi joko ni’le orin, Awon iya ti ni’kan o nii gun wa nibe…” (there are two hundred needles to sit on in the music industry, our mothers have said none shall pierce us) would not be strange to the individual. These lines, it is important to clarify, are ways of paying homage to the people in the spiritual community whose understanding could make their program successful or otherwise. Beyond this appeasement, the lines are expressions of something more. Ideologies in every civilization are usually weaved in religious or social behavior, which people follow and accept because it has become an integral component of their existence. Respect for the elderly is generally emphasized among the Yoruba people. It is believed that the younger ones’ success is assured precisely because they stand on the shoulders of elderly ones who have paved the ways for their greatness. It is therefore important that the elders are celebrated and revered at every opportunity given. Therefore, the ideology of respect is weaved in socio-religious behavior, at which point its generational observation has to blur its social and spiritual lines. Therefore, this respect is performed as a ritual virtually anytime people engage in one thing or the other. From this standpoint, one can understand Ayinla’s repeated invocation of the elders during his performances. Apart from paying homage to the elders who are considered the scaffold of the society, Ayinla, self-named as “President of Music,” was equally encouraging the audience about the primacy of respect in their cultural identity.

These are not an attempt to rid Ayinla of his socially delinquent actions and reprehensible moral involvement. The reinforcement of that piety does not determine how much one can inspire social actions or bring about notable changes in one’s society. The life of Ayinla Omowura did not experience a dearth of socially awkward activities. He was reported to be a chronic user of marijuana, especially when it was yet to receive social acceptance, and this became labeled a vice. The man sufficiently experienced youthful exuberance and was almost carried away by the peer pressure to engage in many socially unacceptable habits.

Definitely, Ayinla established an unbreakable bond between himself and what the conservative segment of his society regarded as indecent moral behavior so much that even after he became successful and popular with his music, he never parted ways with the lifestyle. It was his loyalty to marijuana that brought about some internal contradictions with his band members on different occasions, but it seemed he was more committed to the indulgence even than his members on whose back he rose to prominence. Despite his fidelity to his lifestyle, Omowura refused to allow it to undermine his art. He was spiritedly committed and habits became the spiritual base. He became energized by the history of his father’s engagement. Like his father, music became the ultimate instrument with which to communicate their brilliance with the world. However, he did more than his father. He established the beginning of a musical brand that became an international export.

Ayinla’s life was full of suspense, too, as if a blockbuster movie writer authored it. This probably made TK’s work much easier. The exhilarating part of Ayinla’s life is revealed in the keen competition with other people of similar engagement. During his famous ascendancy, he was competing with Fatai Olowonyo in whose musical prowess was exemplary competence. As already implied, the postcolonial Nigerian environment increased competition among people, especially those whose sources of income were similar. To become the choice of the masses as a musician, one must show an ability to withstand pressures and strives. As a musician, one’s ability to hold competition down is another important attribute that attracted people to one’s activity. The contempt that the detractors nurse against one cannot be allowed to weigh one down; otherwise, one would become the instrument of their greatness while one becomes characteristically useless to one’s ambition. This was the relationship between Ayinla Omowura and his arch-rival, Fatai Olowonyo. However, it is impossible to say that Omowura was a weakling, considering the magnitude of his success while in music.

He was fierce and determined, concentrated on his goals and he used his social environment to create the theatre of musical brilliance. He was precocious, and one cannot deny that his songs are exemplary. Without a doubt, he bossed all his opponents while alive, and there was no contention about his superior career. Perhaps because he was generally different in the ways he commanded music and blended postcolonial issues with them, the relevance of his works in the contemporary time always brings about some questions concerning his foresight.

Ayinla Omowura’s life was controversially electric. No doubt, he was one of those revolutionaries who used their personal life as the template for anti-imperialist agenda. He protested European cultural colonization by actively supporting anything that had the color of his indigenous culture. He was Afrocentric, not only in appearance but also in ideology. He believed in African indigenous epistemic perception and explored it considerably. He was fearless, and his fearlessness made him build a formidable social image for himself so much that people dreaded him, especially those who considered him a potential threat. The potency assured him of Yoruba’s spiritual support system, and because of this, he challenged many of the people he considered enemies. Some people even saw him as a seer. He behaved as if he saw the glimpse of what to happen in the future. According to a local lore, at a point in time, he looked into his band member’s eye, Fatai Bayewumi, and he pointedly told him that he would facilitate his death. In his words, “Bayewumi…Iwo re Judasi; emi re Jeshu; iwo re ma pa mi.” (“Bayewumi, you are Judas; I am Jesus, you will be the cause of my death”). In what would be fulfilled later, Bayewumi eventually was responsible for executing the musical avatar in gruesome ways.

Ayinla Omowura demonstrated his versatility during the 1970s when he continuously produced the songs that gave him the popularity he had even after his demise. He joined the EMI Nigeria in 1970 and produced a piece of very captivating music that same year. His popularity instantly increased with his song titled “Aja To F’oju D’ejo”, and the success recorded in this encouraged him to immediately release three successive singles, all of which combined to give him necessary accolades.

Omowura was not only getting fame; he was increasing in his financial capacity during these years. Market women, drivers, artisans and others found themselves represented well in his songs, which became the reason for their acceptance of him wholeheartedly. There was no indigenous musical expert in Yoruba that rivaled him in social acceptability during his time. The man in question was very productive. He was such an imposing musical figure and maestro that all of his albums were generally accepted. Within his ten years of signing a record deal with the EMI label, his records sold in thousands. For a musician of his background, this is a career stunt that was not easy to pull.

In one of his famous tracks, “Pansaga Ranti Ojo Ola,” Ayinla blended postcolonial issues with African morality, two of which collided at the front of civilization. Pansaga, the Yoruba word for an adulterer or fornicator, was used as a metaphor to teach both the political class and society members. At the surface, one cannot but associate the music to his reproach of sexual immoralities prevalent in the society. He admonished the people selling their bodies to attract economic success for their lack of understanding of their actions’ impending consequences. If one interprets this song in this way, one would not be wrong. However, Ayinla Omowura meant more than this, knowing him as a repertoire of Yoruba knowledge economy who used proverbs and metaphors to teach social lessons. The pansaga, as can be theorized, are the people domiciled in the corridor of power, in the 1970s, for example, who were lacking in the idea of how to manage the booming economy. Just like the woman’s compelling body structure that he alluded to and criticized, the economy was in good condition, but instead of them managing it well for a prosperous future, they were lavishing money endlessly, unconcerned about the probable outcome it would bring. For those who understand the deep-rooted talent of Omowura in using language, they would not doubt the relationship between his songs and the desire to correct social ills. He was seen as a social liberator.

TK has put all my words into a movie. Watch out!